Rhododendron & Azalea News

Caring for Rhododendrons in Winter.

by Steve Henning

Valley Forge Chapter ARS

When winter approaches our rhododendrons exhibit many new characteristics, some good and some bad. When it gets cold our rhododendron's leaves will droop. If it is really cold, the rhododendrons will curl their leaves inward so less leaf surface area is exposed; the plant's trying to keep water from evaporating out of its leaves. Then if it warms up, some buds may begin to open, but this is usually ill-fated and won't amount to much except less flowers in the spring. During cold spells when nothing appears to be happening above ground, the roots can be busy becoming more fully developed and stronger. In the following sections we will investigate why these things are happening and what we should be doing.

When winter approaches our rhododendrons exhibit many new characteristics, some good and some bad. When it gets cold our rhododendron's leaves will droop. If it is really cold, the rhododendrons will curl their leaves inward so less leaf surface area is exposed; the plant's trying to keep water from evaporating out of its leaves. Then if it warms up, some buds may begin to open, but this is usually ill-fated and won't amount to much except less flowers in the spring. During cold spells when nothing appears to be happening above ground, the roots can be busy becoming more fully developed and stronger. In the following sections we will investigate why these things are happening and what we should be doing.

Droop and Curl in Rhododendrons

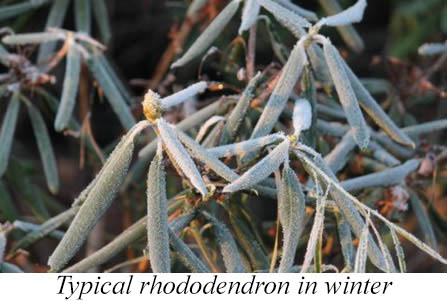

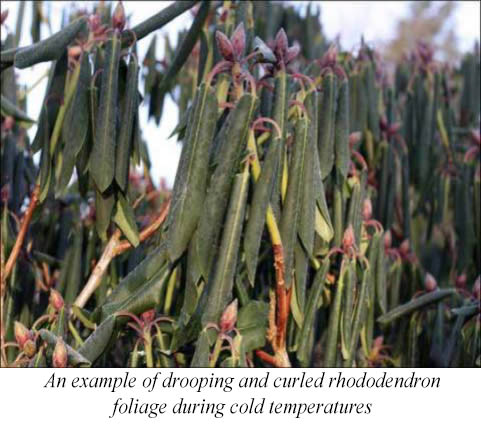

Some rhododendron leaves begin to droop when temperatures drop to around 35°F(2°C). Around 32°F(0°C) the leaves cup and curl at the edges. Around 25°F(-4°C), the leaves will be curled very tight. This problem is not caused by insects or disease but is a way the plant protects its leaves during cold, dry, windy weather. Plants should return to normal when the weather warms again.

In cold weather, high light exposure to rhododendron leaves is detrimental. It damages chloroplasts that are responsible for photosynthesis. However, the rhododendrons that have the ability to droop and or roll their leaves can reduce exposure to light. Such temperature related behavior is called thermonastic leaf movement. The drooping occurs in the petiole (leaf stem). The leaf curl occurs in the leaf itself. So, the temperatures at which these phenomena occur is different. The protection of the photosynthesis producing chloroplasts is important because most photosynthesis in rhododendrons occurs in early spring before the leaves on deciduous trees come out. Some rhododendrons such as R. ponticum don't exhibit thermoplastic leaf movements. For rhododendrons that are cold hardy such as R. catawbiense, a typical response is:

- Above 40°F(4°C): Leaves are open and horizontal to catch the sun's rays

- 40 – 34°F(4 – 1°C): Leaves start to droop, but don't really start to curl yet

- 33 – 25°F(1 – -4°C): Leaves droop all the way down and begin to curl

- Below 25°F(-4°C): Leaves curl up into tight rolls

Leaf curling and leaf drooping are distinct behaviors with different responses to climatic factors and possibly different adaptive significances. Leaf angle is controlled by the hydration of the petiole, as affected by water availability from both the soil and the atmosphere and by air temperature. In contrast, leaf curling is a specific response to leaf temperature, and the leaf hydration state has little effect. The physiological cause of leaf curling is not well understood, but the mechanism must lie in the physiology of the cell wall or regional changes in tissue hydration. The thermotropic drooping of rhododendron leaves most likely serves to protect them from membrane damage due to high irradiance and cold temperatures during the long winters. In addition, the thermotropic leaf curling in rhododendrons may serve to prevent damage to cellular membranes during the process of daily rethawing that often occurs during the early morning.

Leaf curling and leaf drooping are distinct behaviors with different responses to climatic factors and possibly different adaptive significances. Leaf angle is controlled by the hydration of the petiole, as affected by water availability from both the soil and the atmosphere and by air temperature. In contrast, leaf curling is a specific response to leaf temperature, and the leaf hydration state has little effect. The physiological cause of leaf curling is not well understood, but the mechanism must lie in the physiology of the cell wall or regional changes in tissue hydration. The thermotropic drooping of rhododendron leaves most likely serves to protect them from membrane damage due to high irradiance and cold temperatures during the long winters. In addition, the thermotropic leaf curling in rhododendrons may serve to prevent damage to cellular membranes during the process of daily rethawing that often occurs during the early morning.

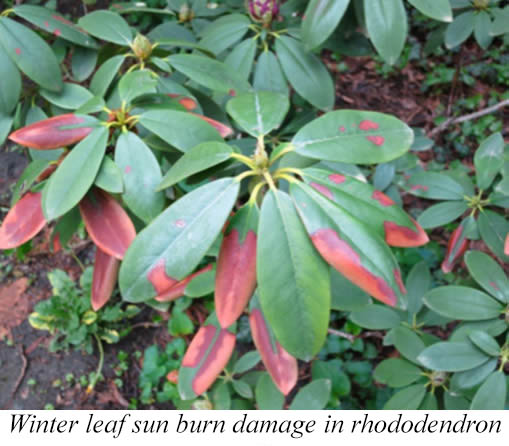

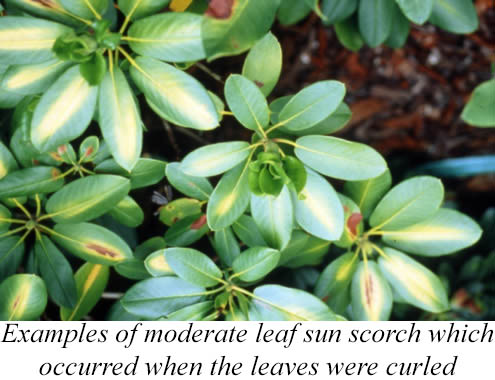

Caring for your rhododendrons through the winter season is easier if you understand how these plants are damaged to begin with. Cold injury in rhododendrons is caused by desiccation, too much water evaporation from the leaves without any to replace it. When cold, dry winds blow across leaf surfaces, they are drying and increase the rate of evaporation. Unfortunately, in the winter it's not uncommon for this to happen when the ground is frozen solid, limiting how much water can be brought back into the plant. Without adequate water levels in their cells, the tips and edges of leaves of rhododendrons will turn brown and die. Rhododendrons attempt to protect themselves from winter dehydration by allowing their leaves to hang down and curling them. This mechanism is often effective, but there are things you can do to help protect your rhododendrons from winter damage. The ideal location of a rhododendron is where it gets some winter shade but early spring sun, and is protected from the winter winds.

Fall and Winter Bloom in Rhododendrons

Some rhododendrons can be easily tricked into blooming in late fall or during winter. The buds usually don't fully open and are not a satisfactory bloom. This basically destroys a bud that would otherwise produce a beautiful flower in the spring. Hence, this trait is undesirable. Dr. Sandra McDonald and others have studied this and found some techniques that may reduce the problem.

Some rhododendrons can be easily tricked into blooming in late fall or during winter. The buds usually don't fully open and are not a satisfactory bloom. This basically destroys a bud that would otherwise produce a beautiful flower in the spring. Hence, this trait is undesirable. Dr. Sandra McDonald and others have studied this and found some techniques that may reduce the problem.

It was observed that fall and winter blooming was most prevalent in plants that had suffered a dry spell before going dormant. This seemed to stop the process that makes flower buds go dormant in preparation for the winter. Then these plants enter the fall and winter without the flower buds being dormant. When the buds are properly hydrated again, they can easily be tricked into blooming. Often this is a time when frosts or winter cold can kill the flowers. Even if they aren't killed, the bloom is seldom satisfactory. Since flower buds are already formed in early summer, the number of buds for spring bloom is reduced. This condition is exacerbated if there is a cool spell in the fall or winter followed by a warm spell which can trick the buds into opening.The corollary to this is to water plants during dry spells to prevent them from enduring a dry spell that interrupts their normal process of flower bud development and the process whereby the buds go dormant. Plants in full sun need more water. One huge caution: make sure you have good drainage and do not overwater. Root rot is a killer of rhododendrons and is caused by roots that are kept too wet, especially in hot weather. A symptom of root rot is the drooping of the leaves, the same symptom as that for being too dry. So, don't be tricked into watering a plant that is too wet already.

The corollary to this is to water plants during dry spells to prevent them from enduring a dry spell that interrupts their normal process of flower bud development and the process whereby the buds go dormant. Plants in full sun need more water. One huge caution: make sure you have good drainage and do not overwater. Root rot is a killer of rhododendrons and is caused by roots that are kept too wet, especially in hot weather. A symptom of root rot is the drooping of the leaves, the same symptom as that for being too dry. So, don't be tricked into watering a plant that is too wet already.

The best solution is to avoid varieties that are susceptible to this problem. In the Hampton, VA area, Dr. McDonald observed these to be the most problematic varieties:

Rhododendrons: Album Elegans, Antoon van Welie, Balta, Belle Heller, Confection, Cunningham's White, Elie, Evening Glow, Everestianum, Graf Zepplin, Kate Waterer, Kevin, Kentucky Cardinal, Mist Maiden, PJM, Princess Juliana, Purple Splendour, Rainbow, Red Cloud, Spring Dawn, Van Nes Sensation, Whitney Orange, Wissahickon, Yak-Corona, R. carolinianum (some), R. dauricum (some), R. hippophaeoides (some).

Evergreen Azaleas: Dorset, Hexe, Opal, Indian Summer.

Deciduous Azaleas: Golden Oriole, Peachy Keen, R. luteum (some).

Root Activity in Winter

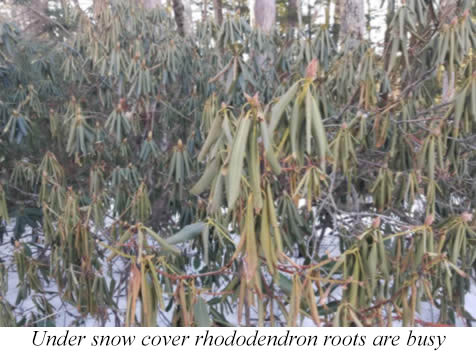

The roots of hardy woody plants don't go completely dormant in winter. Unlike the above-ground parts that pass the winter in dormancy, roots seem to maintain a readiness to grow independent of the above-ground parts of the plant. Roots remain mostly inactive but can function and grow during winter months whenever soil temperatures are favorable, even if the air above-ground part is brutally cold. While roots tend to freeze and die at soil temperatures below 20°F(-7°C), minimum temperatures for root growth are thought to be between 32 and 41°F(0 and 5°C). So, if the soil thaws out and warms slightly, winter roots can break dormancy and become active. This is called "winter quiescence." Roots are resting but ready. This is extremely important for the health of most woody plants. It is this trait that allows evergreen plants to absorb water from the soil and avoid winter desiccation in their leaves, and it is this trait that allows all species, including deciduous hardwoods, the opportunity to expand their root systems in search of water and nutrients in advance of spring bud break.

A woody plant's roots tend to be less cold hardy than its stems and buds. This is fine, so long as the soil is sufficiently insulated by a covering of snow against extremely low air temperatures. A good early season snowfall can keep soil unfrozen throughout the coldest of winters. In such years, sustained winter root activity may replace previously damaged roots, may ready the plant for spring bud break, and may translate into excellent aboveground growth during the following summer.

Conversely, a deep snowpack coming later in winter, after the soil is already frozen, can also insulate the soil in a harmful way. These late snows actually keep soil frozen for extended periods. The surface layers of forest soils do commonly freeze, and when they do, it is not good for roots or the stems and branches dependent on them. Not only do the roots remain inactive under such frozen conditions, but the freezing, heaving, and cracking of winter soils physically damages roots, particularly the fine feeder roots in the uppermost organic layers. This can trigger a cascade of effects on overall plant health. By reducing a plant's ability to take up water and nutrients, particularly during spring bud break, winter root damage limits subsequent stem and branch growth in summer. In turn, this can contribute to plant mortality and may even explain some dead plants. Winter injury to feeder roots is inherent and natural in northern climates.

If the flower buds are failing, that could be wind damage. If the leaves look desiccated, scorched and brown, that could be a combination of winter wind and sun. Because rhododendrons root much more shallowly than other plants, it's extra important to keep a thick layer of mulch over this delicate system. Four inches of an organic mulch, like wood chips or pine needles, is often adequate protection from the cold. It'll also slow water evaporation from the ground, helping your plant stay hydrated. Make sure to give your plants a long, deep drink of water on warmer days so they have a chance to recover from cold snaps.

A windbreak made from burlap, lattice or a snow fence can help slow those drying winds, but if your plant is already planted in a protected area, it should be safe enough from winter damage. A little bit of winter damage is ok; you'll just want to cut out the damaged sections early in the spring so your rhododendron can get back into shape before the bleached leaves become an eyesore. Hence, the ideal location of a rhododendron is where it is protected from cold winter winds, gets some winter shade but early spring sun.

Other Winter Hardiness Factors

Cold hardiness varies from variety to variety. Rhododendrons that are sun-tolerant and grown in the sun are slightly hardier than the same plants grown in partial shade. It is common occurrence that plants grown in partial shade get sun burned when moved out into full sun. Similarly, if rhododendrons are pruned after new foliage has appeared, the foliage that was shaded by the removed foliage will get sun burned. However, enhanced cold hardiness of field grown rhododendrons often is not appreciated enough.

Younger plants are less hardy than mature plants. Normally it takes 5 years from germination for a plant to reach maximum hardiness. Some 2- to 3-year-old plants are as much as 10°F(5°C) less hardy than when mature. I have noticed this in Evergreen Azaleas. It is probably more noticeable since they are often less cold hardy in the first place where I live.

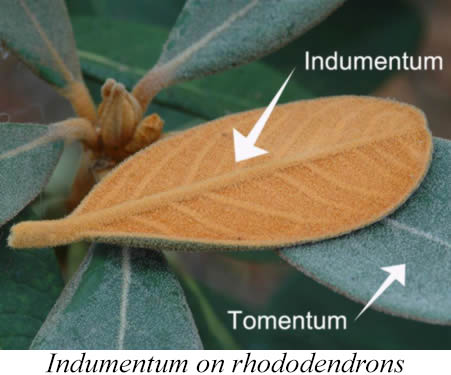

Indumentum is thought to confer some enhancement of cold hardiness. Indumentum is the soft, woolly mat of epidermal hairs found on the underside of leaves in some rhododendrons.  Indumentums can range from white to orange to brown. Some rhododendron leaves, especially young ones, are naturally covered with this wooly mat of hairs. Indumentum is a prized feature of certain species of rhododendrons including yakushimanum. Indumentum protects leaves from environmental stress and from some diseases. It should be left intact and not rubbed off. Stomata and indumentum are both on the reversed side of the leaf. Stomata are the pores from which rhododendrons release oxygen, take in carbon dioxide, and loose moisture. Hence, it is not surprising that indumentum tends to protect the stomata from desiccation. [Fun Fact: floating aquatic plants have stomata on the top of the leaf.]

Indumentums can range from white to orange to brown. Some rhododendron leaves, especially young ones, are naturally covered with this wooly mat of hairs. Indumentum is a prized feature of certain species of rhododendrons including yakushimanum. Indumentum protects leaves from environmental stress and from some diseases. It should be left intact and not rubbed off. Stomata and indumentum are both on the reversed side of the leaf. Stomata are the pores from which rhododendrons release oxygen, take in carbon dioxide, and loose moisture. Hence, it is not surprising that indumentum tends to protect the stomata from desiccation. [Fun Fact: floating aquatic plants have stomata on the top of the leaf.]

In rhododendrons, F2 hybrids are hardier than F1 hybrids. An F1 hybrid is a normal hybrid between two different rhododendrons, species and/or hybrids. An F2 is a second-generation plant that is selfed, that is pollinayed with its own pollen. However, this enhanced cold hardiness in F2 hybrids often takes a while to develop, often 5 years.

Preventing Winter Damage

Proper care during the growing season is a crucial part of keeping rhododendrons alive through the winter. Providing adequate water is essential. For optimum growth, most rhododendrons require one inch of rainfall or supplemental irrigation every week. Avoiding dry conditions is especially important during flower bud development and winter dry spells.

Proper care during the growing season is a crucial part of keeping rhododendrons alive through the winter. Providing adequate water is essential. For optimum growth, most rhododendrons require one inch of rainfall or supplemental irrigation every week. Avoiding dry conditions is especially important during flower bud development and winter dry spells.

However, to prevent root rot, good drainage is even more important. In hot weather, it is better to err on the side of a little too dry since that is when root rot is most likely to become a factor. However, fall watering is extremely important and should continue until the temperature drops below 40°F(4°C). Also avoid fertilizing after mid-July because it may delay dormancy.

Many winter injury issues can be solved by choosing appropriate plants. Hardiness is the first thing to consider. Rhododendrons should be hardy enough to survive in the zone they are planted without too much extra care. Location is just as important as plant selection. Since harsh winter winds and sun can damage rhododendrons, they should be planted in partially shady areas where they are protected from prevailing winds. Generally speaking, avoid planting in dry soil, full sun, or on exposed windy sites. Avoid exposed southern or western sites where winter sun and wind will cause the most damage.

Trouble comes when a plant cannot bring moisture up from the roots due to frozen ground. This can result in a plant with dead, dried out leaves. An anti-transpirant, such as the well-known brand "Wilt-Pruf" can be used. This simple water-based polymer spray is applied in the late fall before the onset of cold. It helps a plant retain moisture in the leaves by covering it with a thin translucent film which does not let the moisture escape. It wears off over the course of several months. It is helpful to apply an anti-transpirant the first winter. Since most plants will not have their roots established fully into the surrounding soil, this spray is a huge help in establishing the plant through this crucial time.

Other important measures include mulching or using physical barriers such as burlap to block the wind. Mulching rhododendrons, especially those that have been newly planted, insulates the soil and protects the plant's roots. At least two inches of mulch should be applied over the root zone, taking care not to pile the mulch against the trunk. Some good mulches are those that are acidic and will not compact...such as pine needles, oak leaves, pine bark chips, pine bark shredded mulch, and evergreen branches. Creating a windbreak with burlap may also help. Never cover the top of the plant. The ideal location of a rhododendron is where it is protected from cold winter winds, gets some winter shade but early spring sun.

But What Can We Do In Winter?

So, assuming we have picked hardy varieties, planted them with appropriate protection from winter sun and wind, and mulched them properly, what is there to do in winter? The main thing is to watch for long dry spells in winter and if the soil is not frozen, water them. Yes, water in winter if necessary. The roots are active when not frozen and need to be kept from drying out. This is especially true for plants that were recently planted. If the subsoil is still frozen, be careful when watering to only moisten the soil and to not drown them.

A final concern in winter is deer damage. When other food is not available, deer will browse on anything green including rhododendrons. There are deer repellant sprays that can be effective if applied often enough. It is best to alternate repellant sprays since deer may get accustomed to one. The other alternative is a physical barrier such as deer fencing or deer netting. One problem with deer netting is that it must be removed in the spring before new growth and flowers grow through it and open, hence trapping the netting.

References:

- Darwin, C. (1880). The Power of Movement in Plants. New York: D. Appleton

- Havis, John (1969). Winter Desiccation Injury of Rhododendron. JARS 23:1

- Nilsen, E.T. (1987). The influence of temperature and water relations ... Plant Physiology 83:

- Nilsen, Erik (1990). Why Do Rhododendron Leaves Curl? Arnoldia. 50:1.

- Nilsen, E.T. (1991). Relationship between freezing tolerance & thermotropic ... Oecologia 87.

- Nilsen, & Tolbert (1993). Does winter leaf curling confer cold stress tolerance in R. JARS 47:2.

- Cordero & Nilsen (2002). Effects of summer drought & winter freezing ... Tree Physiology 22.

- Bird, Kathy (2007). Autumn calls for gardening tips. Rhod. & Azalea News 10:3

- Snyder, Michael (2007). What Do Tree Roots Do in Winter? N. Woodlands 55. 23-25

- Nilsen, et.al. (2014). Thermonastic leaf movements in Rhododendron ... Envir & Exp Bot 106

- Hendrick, Ulysses (2017). Why Rhododendrons Curl and Droop in Winter. shrubbucket.com

- Erier, Emma (2019). Rhododendron Winter Damage. UNH Extension blog

- Nilsen, Erik. (2019). Mini-review of Rhododendron Ecophysiology. Rhod Intl 3.

- Waterworth, Kristi (2020). Rhododendron Winter Care. gardeningknowhow.com