Culture: How To Grow

Culture: How To Grow Culture: How To Grow

Culture: How To GrowI. Variety: The rhododendron or azalea must be suitable for the climate where it is planted. Some varieties are too tender for harsh winters, too tender for very hot weather, too sensitive to droughts or wet conditions. For specific problems, visit Cold Resistance. Select the variety for the location. Different varieties grow different heights. Some are tall, over 6', and some are dwarf, barely 12", and many are in between. Unfortunately, most rhododendrons never stop getting taller, but their height is quoted for plants that are 10 years old and by that time most varieties have slowed down their growth considerably. But if you choose plants that are the right size to begin with, they are relatively maintenance free. The American Rhododendron Society website has good charts for rhododendrons and azaleas giving the hardiness and height. Another very useful chart on the ARS website are the Proven Performer Lists that lists the favorite rhododendron and azaleas plants for different parts of the US and Canada.

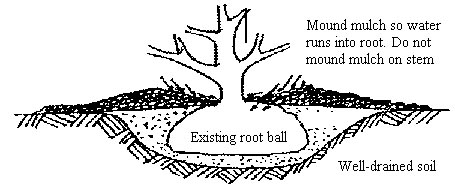

II. Soil Drainage: Because the fine roots of azaleas and rhododendrons are easily blocked by fungi, excellent drainage is important. To test drainage, dig a hole 6 inches deep in the bed and fill it with water. If the water has not drained from the hole in four hours, install drainage tile to carry away excess water, or build raised beds. Moist well-drained soil is a must for most varieties. This sounds difficult, but it means to not let the soil dry out completely but don't get it too wet. Thoroughly water if necessary and then let it become almost dry. Most gardeners do this by planting in a well-drained area and mulching to hold the soil moisture in. Watering is seldom necessary except during long dry periods. For specific problems, visit Watering.

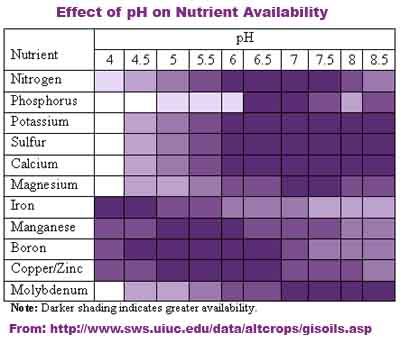

III. Acid Soil: Most varieties require an acidic soil (pH 4.5-6). Powdered sulfur is the best agent to acidify the soil. Holly-tone has this in it. Your plants will get chlorotic if the soil is not acidic enough. For specific problems, visit Soil Requirements and pH.

IV. Fertilizing: When rhododendrons and azaleas are not planted in ideal locations they may develop chlorosis. Chlorosis is yellowing of a leaf between dark green veins. It is caused by malnutrition that can be caused by a wide variety of conditions. They include alkalinity of the soil, potassium deficiency, calcium deficiency, iron deficiency, magnesium deficiency, nitrogen toxicity (usually caused by nitrate fertilizers) or other conditions that damage the roots such as root rot, severe cutting of the roots, root weevils or root death caused by extreme amounts of fertilizer. In any case, a combination of acidification with sulfur and iron supplements such as chelated iron or iron sulfate will usually treat this problem. Holly-tone contains these elements and 4-6-4 fertilizer. It is best applied in the spring prior to blooming to make sure the plant is healthy when forming next year's flower buds. If you missed applying it in the early spring, it can be applied up until mid summer. Rhododendrons do best when left alone in the right conditions. You don't need to use Holly-tone or any fertilizer unless the plant shows signs of malnutrition. For specific problems, visit Fertilizing.

V. Shade: Some shade; some varieties like full sun to bloom but others suffer from too much sun. This is a trial and error thing unless you know the variety and can look it up. More sun stimulates flowering and but may trigger lace bug infestations. Prune off lower branches of shade trees so that you have "high shade" above your rhododendrons. This is ideal for a healthy rhododendron bed. For specific problems, visit Sun & Shade and Shade-loving Rhododendrons.

VI. Mulching: Rhododendrons do best when they have about a 2" to 3" layer of mulch to hold in moisture, prevent weeds, and keep the roots cool. Since most mulches are organic, they need to be topped off periodically, usually about every year or two. Do not make the mulch over 3" thick. Keep the mulch about 2" to 3" back from the trunk/stem of the plants to avoid bark split and rodent damage. Do not use peat moss as a mulch. It is a soil amendment to be used when preparing the soil in a bed and can cause severe problems when used as a mulch including dehydrating the soil and preventing moisture from reaching the soil. It also tends to blow around. It is best to mulch with a 2-inch layer of an airy organic material such as wood chips, ground bark, pine needles, pine bark or rotted oak leaves. A year-round mulch will also provide natural nutrients and will help keep the soil cool and moist. For specific problems, visit Mulching.

VII. Protection: In choosing a location to plant rhododendrons and azaleas, protection is very important. Protect from winter winds. This is especially true when the ground is frozen. Also protect from deer. I use deer netting in the winter and for plants that are susceptible to damage in the summer, such as deciduous azaleas, I have a couple beds protected by deer fencing. For specific problems, visit Cold Resistance and Deer Protection.

VIII. Propagation: Propagation of rhododendrons and azaleas is usually done by commercial nurseries, but is also successfully done many gardeners. There are several methods:

IX. Cultural Problems: Most problems are cultural. Some tender rhododendron & azalea varieties are not suitable for growing outside green houses. Cultivating rhododendrons and azaleas must be avoided. They have shallow roots and the roots will be severely damaged by cultivating. Weed killer from weed & feed products is a definite problem also. Salt from sidewalks in the winter is a killer to azaleas. Soil near masonry such as foundations and walks is usually alkaline (not acidic) and a problem. Lawn fertilizer in the fall can set an azalea way back. Another problem is the roots of walnut trees. They emit a chemical that is toxic to rhododendrons, azaleas and many other kinds of plants. For specific problems, visit Common Problems and Their Solutions.

X. Transplanting: Move plants that are planted in the wrong location. Some rhododendrons like more sun and some like more shade. If you didn't note this before planting, the plants may be struggling and should be moved to a better location. Rhododendrons are easy to move. They have shallow roots. Don't place the rhododendrons close to shallow-rooted trees such as maple, ash or elm. Feeder roots from such trees rapidly move into improved soil and compete for water and plant food. When transplanting a large plant several steps should be followed. First, it is best to stimulate a tight root ball by root pruning the plants to be moved about a year before moving. This is accomplished by cutting a circle around the plant stem with a shovel to cut off roots that extend beyond this point. This radius is usually slightly smaller than half way to the drip line. Second, it is best to move when the plant is dormant and not stressed. This would be in the spring and fall when the plant is still dormant but the soil is not frozen. Moving in the fall before the ground freezes is preferable if you don't have a problem with frost heaving. Sometimes winter freezing and thawing cycles can actually lift a transplanted plant out of the ground where the roots are then desiccated and the plant dies. For this reason, it is safer to transplant in the spring after the ground thaws in climates where frost heaving is a problem. Third, take precautions to preserve the integrity of the root ball. Tie the ball together and support is so it doesn't fall apart. The very safest approach is to dig a trench up to 12 inches deep, around the drip-line of the plant. Then undercut the plant to form a cone, removing the soil an inch or so at a time, moving all around the plant, until you begin to see that you are removing roots. If possible, then get a square of burlap under the plant. Tilt the plant to one side, put one edge of the burlap close to the center of the plant, wadded up so that only half of it is on the open side of the plant, then rock the plant the other way and pull the burlap through. Tie the corners of the burlap to each other across the plant. Tie the burlap tightly to keep the soil around the plant roots undisturbed. Then lift the plant by the burlap and the bottom, not by its stems. Finally, pruning the top helps match the demands of the top to the capability of the roots after they are stressed by the move. People have been known to cut the top off wild rhododendrons before moving and the plants have come back with superior shape. This is drastic and not recommended for a plant you don't want to risk loosing. Rhododendrons and azaleas have dormant buds beneath the bark, which sprout to form new growth after severe pruning, hence severe pruning, which removes 1/3 to 1/2 of leaf area, is quite common when transplanting. Make sure you watch the plant after it was moved like you would a new plant. Its roots are compromised and it will need a reliable source of moisture. If the weather has a dry spell, make sure you water any newly planted rhododendrons, large or small. For specific problems, visit Transplanting.

All rhododendrons and azaleas will grow well in light shade. Most rhododendrons including the Carolina rhododendron will bloom more abundantly in full sun if the soil is kept moist, but sunscald and winter desiccation problems may cause foliage and bud problems. More sun stimulates flowering and but may trigger lace bug infestations. In hot climates or in windy places partial shade is usually mandatory. Also, full sunlight tends to bleach the flowers. In cold climates, most rhododendrons do better on the north side of a building or on a northwest slope where they receive protection from the winter sun. All rhododendrons and azaleas need some sun for best flowering but in general require partial shade. These requirements vary between varieties and also vary in different climatic zones.

Flowering: Rhododendrons and azaleas usually won't flower well if planted under trees with dense foliage, such as maples, beeches, and pines. Plant in the diffused light under widely spaced, high-crowned trees like oaks and tulip poplars. Prune off lower branches of shade trees so that you have "high shade" above your rhododendrons. This is ideal for a healthy rhododendron bed.

Sun Tolerance: In the southern USA where sun tolerance is a greater requirement, the most popular plants are azaleas, especially in the Southeastern states. However, in Oklahoma, some growers have been successful growing rhododendron iron-clads. Though iron-clads are most noted for their winter hardiness, many also exhibit good sun tolerance. The American Horticultural Society has created a Heat Zone Map. This should be helpful in determining if a plant grown in one area will have the same heat tolerance in a different area. I haven't seen any work using this map with rhododendrons and azaleas. However it is valuable to let us compare regions. Also see Shade-loving Rhododendrons.

Plant Cold Hardiness: A study in New England determined that a plants hardiness rating varies by about 10 degrees from winter to winter. A decrease in hardiness is usually caused by warm spells followed quickly by very cold spells. The hardiness rating that is reported is usually the lowest temperature a plant has been known to survive without damage. In the real world, the actual capability may be 10 degrees warmer than that some years. Some rhododendrons can tolerate severe winter conditions while others cannot. There are two problems from cold:

1) cellular damage caused by freezing when plant is not hardened off properly or is too tender a variety for the temperature. To harden off properly a plant must be allowed to go dormant in the fall. New growth is the most susceptible. This means that fertilizers containing nitrogen shouldn't be applied after mid summer since nitrogen fertilizers encourage new growth. If the weather is warm in the fall before early frosts, this is an idal time to see freeze damage. The two photos to the right show examples of severe freeze damage and mild freeze damage. [Photos are courtesy of Harold Greer]

2) desiccation of the foliage when the ground is frozen and sun and wind attack the leaves. There are four solutions:

- cold-resistant varieties of plants

- winter windbreaks

- winter sun shade

- chemical antitranspirants

Cold Hardiness Zones: In catalog listings, the cold resistance of a hybrid rhododendron is usually indicated by a code that indicates the lowest temperature the flower buds can tolerate during the winter and still open perfectly in the spring. The US Department of Agriculture introduced Plant [Cold] Hardiness Zones in 1960 to classify the cold hardiness required of plants in certain areas. Prior to USDA Zone system, there was an international cold hardiness rating system for rhododendrons which ranged from H-1 to H-5. Plants bearing the code designation H-1 do well down to -25°, H-2 to -15°, H-3 to -5°, H-4 to 5°, H-5 to 15°, H-6 to 25° and H-7 to 32°. Most varieties grown in the USA range between H-1 and H-4 in hardiness. Many catalogues use to the USDA cold hardiness zones. Zone 4 corresponds to H-1, Zone 5 to H-2, Zone 6 to H-3, Zone 7 to H-4, Zone 8 to H-5, etc. Other factors are important. If your plants are subject to desiccating sun and wind in the winter or warm spells in winter that may compromise a plants dormancy which, then you should probably use plants that are one zone hardier. For example, I live in Zone 5, H-2, but try to use plants that are good for Zone 4, H-1. Plants with a H-2 rating need winter protection.

There is a third cold hardiness zone system developed by Sunset Magazine for 13 states in the Western US. It is completely different and tries to divide the West into 24 plant zones. If you are using a Sunset Magazine garden book then you will have to become familiar with this system. That is about the only place it is used. Apparently, even though the climate zones were established by the University of California Cooperative Extension, the Sunset Magazine climate zone map is copy written so it was never intended to be used outside Sunset Magazines own publications.

Heat Hardiness: Also, heat hardiness in the summer is an issue which needs to be considered.

Winter Wind: Rhododendrons may be harmed in winter by drying winds and bright sun; protect their shallow roots with a mulch of oak leaves or pine needles and their foliage with a loose blanket of evergreen boughs or specially built screens. Such screens must provide shade without capturing heat. A burlap screen will protect a plant while a black or clear plastic bag will cook a plant. Keep the mulch away from the trunk of the plant. This avoids bark split, fungus and rodent damage.

Antitranspirants: Chemical antitranspirants effectively cover the stomata, the pores through which the leaves loose moisture. However they must be designed to naturally degrade so they don't interfere with the normal operation of the stomata during the growing season. This usually means the antitranspirants need to be applied at least twice during the winter, but not too close to the growing season.

Dormancy: To insure that a plant has the ability to make it through the winter, it must be dormant. Dormancy is a normal process in which the plant goes into a rest state during the winter. Dormancy is caused by a number of things including short days, low temperatures and drought. Several things can break or prevent dormancy.

The most important factor in achieving vigorous growth is an acid soil mixture high in organic content. Rhododendrons and azaleas need an acid soil with a pH of 4.5 to 6.0, well mulched with organic material. Rhododendrons thrive in a moist, well-drained, humus-filled soil, enriched with peat moss or leaf mold. You only need to amend the soil if it is devoid of organic matter or if the pH is too high. Have a soil test done by your local extension service to determine if something needs to be added. Well-decayed organic matter dug into the top layer of soil is helpful for retaining moisture and preventing compaction. For organic matter you can use loam, coarse sand and ground oak leaves or sphagnum peat moss. Many commercial growers root rhododendrons and azaleas in pure sphagnum peat, or in a 50-50 mixture of sphagnum peat and coarse sand or perlite. A favorite mixture on the West Coast is 1/2 sphagnum peat and 1/2 ground bark dust, but in such mixtures, plants must be fed regularly. My favorite soil mix is a 50-50 mix of peat humus and the natural soil. Soil around the rhododendron's shallow roots must be kept cool and moist but well drained.

Sphagnum peat or peat moss is a super soil amendment. Researchers claim that plants planted in mixes containing sphagnum peat will resist disease better. The sphagnum peat in the soil does regulate the availability of water so the roots are not too wet, but also the sphagnum is said to provide protection against disease.

Soil pH: Soil pH is a measure of the acidity of soil in terms of activity of hydrogen ions (H+). Since the pH is actually the magnitude of a negative exponent, a smaller number means more acid. A pH of 7 is neutral, while a pH of 0 is strongly acidic and 14 is strongly alkaline. One way of determining pH in native soils is to observe the predominant plants. Calcifuge plants (those that prefer an acidic soil) include Erica, Rhododendron and nearly all other Ericaceae species, many Betula (birch), Digitalis (foxgloves), gorse, and Scots Pine. Calcicole (lime loving) plants include Fraxinus (Ash), Honeysuckle (Lonicera), Buddleia, Cornus spp (dogwoods), Lilac (Syringa) and Clematis spp. The mophead hydrangea (Hydrangea macrophylla) produces pink flowers at pH values of 6.8 or higher, and blue flowers at pH 6.0 or below. pH is not constant in soil or water, but varies on a seasonal or even daily basis due to factors such as rainfall, biological growth within the soil, and temperature changes. Slightly acidic soils (pH ~6.5) are considered most favorable for overall nutrient uptake. Such soils are also optimal for nitrogen-fixing legumes and nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria. Some plants are adapted to acidic or basic soils due to natural selection of species in these conditions. Rhododendrons and azaleas prefer soils with a pH of 4.5 to 6.0. Potatoes grow well in soils with pH <5.5. Blueberries and cranberries grow well in even more acidic soils (<4.5) . Many farm crops including sugar beets, cotton, kale, garden peas, and many grains and grasses grow well in alkaline soil (>7.5). A soil test, available for a nominal fee through your local county Extension office, will determine the pH and nutrient content of your soil and provide recommendations for fertilizer. When grown in soils having a pH above 6.0, plants may appear anemic when certain nutrients such as iron become deficient.

Soil pH: Soil pH is a measure of the acidity of soil in terms of activity of hydrogen ions (H+). Since the pH is actually the magnitude of a negative exponent, a smaller number means more acid. A pH of 7 is neutral, while a pH of 0 is strongly acidic and 14 is strongly alkaline. One way of determining pH in native soils is to observe the predominant plants. Calcifuge plants (those that prefer an acidic soil) include Erica, Rhododendron and nearly all other Ericaceae species, many Betula (birch), Digitalis (foxgloves), gorse, and Scots Pine. Calcicole (lime loving) plants include Fraxinus (Ash), Honeysuckle (Lonicera), Buddleia, Cornus spp (dogwoods), Lilac (Syringa) and Clematis spp. The mophead hydrangea (Hydrangea macrophylla) produces pink flowers at pH values of 6.8 or higher, and blue flowers at pH 6.0 or below. pH is not constant in soil or water, but varies on a seasonal or even daily basis due to factors such as rainfall, biological growth within the soil, and temperature changes. Slightly acidic soils (pH ~6.5) are considered most favorable for overall nutrient uptake. Such soils are also optimal for nitrogen-fixing legumes and nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria. Some plants are adapted to acidic or basic soils due to natural selection of species in these conditions. Rhododendrons and azaleas prefer soils with a pH of 4.5 to 6.0. Potatoes grow well in soils with pH <5.5. Blueberries and cranberries grow well in even more acidic soils (<4.5) . Many farm crops including sugar beets, cotton, kale, garden peas, and many grains and grasses grow well in alkaline soil (>7.5). A soil test, available for a nominal fee through your local county Extension office, will determine the pH and nutrient content of your soil and provide recommendations for fertilizer. When grown in soils having a pH above 6.0, plants may appear anemic when certain nutrients such as iron become deficient.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Do not use Aluminum Sulfate: If you google "aluminum sulfate rhododendron azalea" you will find some extension agents still recommending aluminum sulfate while most are warning against using it. It is sad that such bad advice is still being given.

Never use aluminum sulfate for making the planting medium more acid. Thousands of azaleas and rhododendrons are killed each year by the addition of aluminum sulfate to planting mediums. Aluminum ions under very acid conditions are very toxic to all of the rhododendron genus.

Aluminum is not considered to be an essential element for plant growth. In fact, for most plants, high levels of available soil aluminum are toxic causing stunting of root growth and eventual death if soil aluminum is high enough. Usually the soil pH has to be less than 4.5 for this to happen. Rhododendrons and azaleas are more vulnerable than many other plants.

Although aluminum sulfate often is recommended to gardeners for increasing the acidity of the soil, it has a toxic salt effect on the roots of plants if it is used in large amounts. Small amounts are not very effective. About 7 lb. of aluminum sulfate are required to accomplish the same effects as one lb. of sulfur.

The one area where aluminum sulfate is recommended is in making blue hydrangeas blue. The chemistry of hydrangeas is such that not only acidity is necessary, but aluminum ions are also necessary to make the flowers blue due to the aluminum binding with the anthocyanin. Hence, blue hydrangeas shouldn't share the same beds with rhododendrons and azaleas. Over application of aluminum sulfate can be toxic even to hydrangea.

I am sure that part of the reason for the bad advice is that aluminum sulfate is very quick in modifying the soil pH. Sulfur is very slow, but is much more effective eventually.

Guy Nearing was one of the first to realize that aluminum sulfate was detrimental to rhododendrons and azaleas. His findings were published in the Journal of the ARS in 1955.

Rhododendrons are Vanishing by Guy Nearing

Today, the effect is thoroughly understood. The most eloquent article on adjusting soil pH for rhododendrons and azaleas was written by Sandra Mason with the University of Illinois, Champaign, slmason@uiuc.edu.

How to Lower Soil pH (and how not)

In her words, "Many acres of land in the world are unusable for crops due to soil acidity and aluminum toxicity."

Bed Preparation: Because the roots grow typically within 2 or 3 inches of the surface, a bed prepared especially for rhododendrons and azaleas need not be more than 12 inches deep; deep planting or too much mulch in the growing season keeps the roots from getting the air they need. In fact, it is a good idea to set rhododendrons about 1 inch higher than they grew at the nursery. Balled-and-burlaped plants may be planted while in blossom but it is better to transplant them when they are dormant.

When to Plant: Whether to plant in spring or fall is always a question. Fall planting is best because it is less stressful to the plant than spring and summer planting. During the fall, temperatures are cooler and plants are going dormant. As top growth decreases, there is less demand on the roots for water and nutrients. Roots continue to grow and become established throughout the fall and winter months, however, even when the top is dormant. By spring, the well-established roots are ready to support new growth and flowers.

Moisture: When the shallow root system can't take in all the water it may need to survive such as during a summer dry spell, this can spell disaster. Do not allow the roots to dry out, but good drainage is essential also. Mature plants are much hardier and Mother Nature seems to take good care of them under normal conditions. Care for new plants for 2-3 years to help them get established. One problem with fall planting is that it makes a plant more susceptible to frost heave in climates where freezing and thawing cycles are common. In that case, rhododendrons are best planted in the spring. It must be noted that maintaining the proper moisture level in the summer is more difficult after spring planting.

Buying Plants: When buying plants in the fall, it is risky to buy potted plants or balled and burlapped plants that were in a garden center all summer. It is best to buy field grown plants that are freshly dug. However, most plants are purchased in the spring when they are in bloom. Just be advised that this is the least favorable time to plant them. Most will be OK if planted properly and carefully watched during the heat of the summer, but the rate of loss is higher. Return to Top

Azaleas will not survive in wet, poorly-drained soil. Avoid planting them in depressions where water may puddle after rain or near downspouts where they experience wet/dry fluctuations in soil moisture. Dig a hole the depth of the pot or root ball and fill it with water. If the hole drains within an hour you have good drainage. If the water has not drained out of the hole within one hour, the soil is poorly drained and you must correct the drainage problem before planting. Install a perforated pipe or drain tile in the garden, making sure that the outlet is lower than the bottom of the planting hole, or build raised beds.

Turn the soil well and dig a hole two or three times as wide as the root ball. Add plenty of organic material, remove the plant from its container and loosen the root ball. Water the pot thoroughly before planting and tease the soil away from the roots on the outside of the pot. Don't worry about injuring the roots it's more important to remove a significant amount of the potting soil than it is to keep every root intact. Planting depth is critical because azaleas are shallow-rooted plants. In sandy soils, set the root ball in the hole so the top is about 1 inch above the surrounding soil grade. In clay soils and poorly drained soils, place the top of the root ball 2 to 4 inches above the soil grade, gradually sloping the soil to meet the original grade. This allows for settling and assures that the roots will be in the upper layer of soil where they can readily obtain oxygen, water and nutrients.

Set the root ball into your prepared hole (making sure the top 1-2 inches of the ball is above the soil level), pull in your humus/organic soil around the plant, pack firmly and cover with mulch. Finally, water the whole area thoroughly and apply a thin layer of shredded leaves, pine needles, or pine bark to keep the soil cool and moist. Water your newly planted rhododendron or azalea weekly if the weather is dry, at least for the first year.

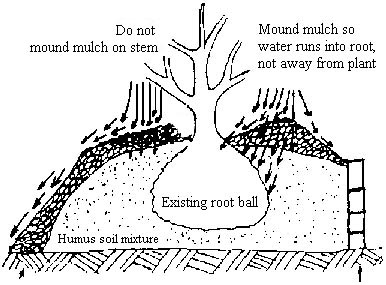

Raised Beds: Rhododendrons and azaleas need three things, acidic soil, drainage and drainage. If the soil is poorly drained or alkaline, a raised bed may be the best option. Rhododendrons and azaleas have shallow roots, so the raised bed only needs to be 6 to 12 inches above grade. Create it by creating a mound or berm, or a raised planting bed using a retaining curb such as logs, timbers or rocks. It is best if the base is a material with good drainage like gravel. Then at least 6 of 8 inches of good acidic, well-drained soil above that. If you use a lot of peat moss or compost remember, the peat moss and compost will decompose over time to 1/2 the original depth, so make the bed proportionately deeper. [Sketch courtesy of Harold Greer]

Raised Beds: Rhododendrons and azaleas need three things, acidic soil, drainage and drainage. If the soil is poorly drained or alkaline, a raised bed may be the best option. Rhododendrons and azaleas have shallow roots, so the raised bed only needs to be 6 to 12 inches above grade. Create it by creating a mound or berm, or a raised planting bed using a retaining curb such as logs, timbers or rocks. It is best if the base is a material with good drainage like gravel. Then at least 6 of 8 inches of good acidic, well-drained soil above that. If you use a lot of peat moss or compost remember, the peat moss and compost will decompose over time to 1/2 the original depth, so make the bed proportionately deeper. [Sketch courtesy of Harold Greer]

When preparing new raised beds in soil that is not acidic, the pH may be lowered by adding flowers of sulfur (powdered sulfur). Amounts of powdered sulfur needed to lower the pH of a silt loam soil to a 6-inch depth are given in the table above. A target pH of 5.5 is ideal for most rhododendrons and azaleas. Sandy soils would require less and clay soils would require more. Elemental sulfur is converted to sulfuric acid by soil bacteria. Therefore, in order for sulfur to work the following must be satisfied:

Root pruning: Most rhododendron and azalea plants sold at nurseries and garden centers are sold in containers or have a root-ball that is covered with burlap. These plants have a potentially serious problem when the roots reach the container and start circling inside the pot. They become pot bound or root bound. These roots must be cut so they don't continue to grow and start strangling other roots. Many apparently healthy plants die when the roots start strangling each other. To prevent this, it is necessary to remove the plant from the container and and examine their roots. If the plants appear pot-bound and have a thick, dense mat of fibrous roots along the surface of the root ball, used a knife to make three to six vertical cuts, about 2 inches deep, equally spaced around the sides of the root ball. Then use your hands to gently loosen the roots where cuts were made and pull the roots outward. This process stimulates new root growth and allows water and nutrients to penetrate into the root mass. If the roots are not pot-bound, it is not necessary to slice them with a knife, but it is beneficial to loosen and pull them outward with your hands. When working with roots, make sure the plant is thoroughly watered. Any roots that dry out will die.

If the plant has been transplanted several times it may be necessary to remove all soil so that previous areas that were pot bound in side the root ball when it was planted in smaller containers my be exposed. All roots must be separated so the only go in one direction and do not circle. Those that cannot be straightened must be cut. If allowed to circle other roots, they will strangle the other roots as they grow larger. When working with bare roots of a plant, keep them moistened. Any roots that dry out will die. Return to Top

When planting balled-and-burlaped plants, if you are not sure the burlap is natural and not treated, remove the burlap. In years past, a natural burlap was used that would rot in the soil. Today, preservatives are added to the burlap to make it last longer. This hampers root growth and may lead to the early demise of a plant. If you do get a plant with natural burlap, then make sure you loosen the burlap and push it down as far as you can into the hole. If it comes to the surface, it will wick moisture out of the ground. Before planting, make sure you soak the root ball about an hour. A dry root ball is difficult to re-wet once it is in the ground. To plant a balled-and-burlaped plant:

Before planting, make sure you soak the root ball about an hour. A dry root ball is difficult to re-wet once it is in the ground. When planting containerized plants:

Followup: Do not fertilize at the time of planting, as this might injure the roots, but water deeply. Also, if newly purchased plants have little white BB-like balls in its container don't even think of fertilizing for a while. The little balls are fertilizer and those plants have been pushed to the hilt. Plant them as soon as possible and let them adjust. Plants that have been given a soil mixture rich in organic matter probably will not need feeding for several years. Wait until the plants are established before fertilizing them.

Apply 3 to 4 inches of an organic mulch such as pine straw, pine bark mini-nuggets or shredded leaves on the surface. Use your hands to pull the mulch away from the trunk an inch or two. This helps keep the trunk area dry and reduces the chances of wood decay. It also discourages rodents from gnawing on the trunk. Organic mulches gradually decompose and provide nutrients to the plants.

Whether the plant was balled-and-burlaped or potted, make sure that the plant is getting wet. As mentioned in the previous section, rhododendron guru Harold Greer noted: "Quite often a plant will get completely dry and then no matter how much water you apply, the rootball will just keep shedding it. The top of the soil may seem wet, and the soil around the plant may even be very wet, but the actual rootball of the plant is bone dry. This is especially true for newly planted rhododendrons, and it is the major reason for failure, or at least less than great success with that new plant. It is hard to believe that a plant can be within mere inches of a sprinkler that has been running for hours and still be dry, yet it can be SO TRUE!"

Most rhododendron and azalea plants sold at nurseries and garden centers are "hardy", grown to be planted outdoors in the climate of the nursery or garden center. These plants are usually quite easy to transplant but some precautions are important to insure success.

Because the roots grow near the surface, a bed prepared especially for rhododendrons and azaleas need not be more than 12 inches deep; deep planting or too much mulch in the growing season keeps the roots from getting the air they need. In fact, it is a good idea to set rhododendrons about 1 inch higher than they grew at the nursery. Balled-and-burlaped plants may be transplanted in blossom but it is better to transplant them when they are dormant.

Whether to transplant in spring or fall is always a question. Fall is normally the best time because roots on a new plant need help establishing themselves. The shallow root system can't take in all the water it may need to survive and a drought can spell disaster. Water them frequently in the morning. Mature plants are much hardier and Mother Nature seems to take good care of them under normal conditions. Care for new plants for 2-3 years to help them get established. One problem with fall transplanting is that it makes a plant more susceptible to frost heave in climates where freezing and thawing cycles are common. In that case, rhododendrons transplant best in the spring. It must be noted that maintaining the proper moisture level in the summer is very difficult after spring transplanting. Make sure you watch the plant after it was moved like you would a new plant. Its roots are compromised and it will need a reliable source of moisture. If the weather has a dry spell, make sure you water any newly planted rhododendrons, large or small.

Make sure that the plant is getting wet. Rhododendron guru Harold Greer noted: "Quite often a plant will get completely dry and then no matter how much water you apply, the rootball will just keep shedding it. The top of the soil may seem wet, and the soil around the plant may even be very wet, but the actual rootball of the plant is bone dry. This is especially true for newly planted rhododendrons, and it is the major reason for failure, or at least less than great success with that new plant. It is hard to believe that a plant can be within mere inches of a sprinkler that has been running for hours and still be dry, yet it can be SO TRUE!".

Some rhododendrons like more sun and some like more shade. If you didn't note this before planting, the plants may be struggling and should be moved to a better location. Rhododendrons have shallow roots; they are easy to move.

When transplanting a large plant several steps should be followed.

People often ask, can I plant my Mother's Day azalea (or other gift plant purchased from a florist) outdoors.

Greenhouse Azaleas: Florist Azaleas, and other greenhouse azaleas which are forced to bloom for special holidays, are varieties hybridized to be easy to propagate and easy to force into bloom at a precise time and with very showy foliage and flowers which tend to hold well. In most climates they do not do well outdoors and are considered to be houseplants.

Garden azaleas are species or varieties which are hybridized to not force easily since they can be faked out by unseasonable weather and sport which destroys the seasonal bloom. They are also selected or bred to be hardy for certain climates such as hot climates, cold climates, wet climates and dry climates. They do not do well as house plants since they need normal seasonal changes to properly produce and open flower buds.

Care: A greenhouse azalea needs regular watering. Check it every couple days to make sure it is moist. When the top layer of soil in the pot feels dry to the touch , water the plant thoroughly (best done in a sink over a rack) and allow it to drain freely through the drainage holes in the bottom of the pot. If the plant was watered over a saucer, be sure to drain it after 15 minutes. A great way to double check whether you should water the azalea is to lift the plant periodically, comparing its weight to how heavy it seemed after you last watered it. Eventually you will know when it's ready to be watered, just by lifting the pot.

If the plant gets too dry, wait about 15 minutes after the first watering and repeat watering in the same way. If the plant still feels light when you lift it you may need to plunge the whole potted plant into a pail of water and allow it to soak until no more bubbles appear. Unfortunately when an azalea is allowed to get this dry it almost always drops a lot of leaves soon after and may even die.

While the azalea is blooming, keep it close to a window where it can receive at least 4 hours of indirect sunlight per day. Try to keep temperatures as close to ideal as you can. Night temperatures between 45° and 55° F and day temperatures that do not exceed 68° are the goal. Since this plant requires low night temperatures, it will probably have to be set in a cool entranceway or enclosed porch during the evening. The plant will probably tolerate a less than ideal location for a few days as long as you return it to a better place shortly thereafter. There is no need to fertilize while the plant is blooming.

Unlike other shrubs in the landscape, azaleas are shallow rooted and can be easily injured by excess fertilizer. In fact, some experienced azalea growers do not apply chemical fertilizes at all. They have found that plants usually can obtain sufficient nutrients for growth and flowering from the organic matter added to the planting hole and from the decaying mulch on the soil surface.

Chlorosis: Fertilizers, however, are occasionally needed. Pale green leaves or inter-veinal chlorosis are good indicators of a need for fertilizer. If you do fertilize, avoid using general garden fertilizers for rhododendrons, azaleas and other acid-loving plants. Use those specially formulated for acid-loving plants and follow directions. Fertilizers supplying the ammonium form of nitrogen are best.

How: Rhododendrons and azaleas grow well naturally at relatively low nutrient levels. Therefore, fertilization should be done carefully, or the fine, delicate roots close to the soil surface will be damaged. A fertilizer analysis similar to 6-10-4 applied at 2 pounds per 100 square feet to the soil surface is usually adequate. Cottonseed meal is also a good fertilizer.

Fertilizing our outdoor plants should be done in May, but not after July 1. Late summer fertilization may force out tender fall growth that will be killed by the winter. Broadcast fertilizer over an area extending 4 to 6 inches from the trunk to beyond the dripline or edge of the canopy. Be careful when broadcasting fertilizer over the top of plants, because the fertilizer granules may collect in the leaf whorls and cause foliar damage as it dissolves. Always fertilize when the foliage is dry, then use a broom or rake to brush residual fertilizer from leaves or stems. Apply overhead irrigation soon after application to wash any residual fertilizer from the foliage and to dissolve the fertilizer applied. Do not remove the mulch when fertilizing. The fertilizer will dissolve and move through the mulch with irrigation water and rain.

When: For most garden situations the old rule "once before they bloom and once after they bloom" is still a sensible approach. Actually the fertilizer timing has nothing to do with the time the plant flowers, it simply means once in the early spring, probably April then again in June. Never fertilize after mid-summer. Over-fertilizing is worse than not fertilizing at all. Established azaleas often do well with no fertilizer at all. Nutrients are slowly released by any organic mulch that you use, so rely on this as the primary source of nutrients. Excess nutrients may promote larger than normal populations of azalea pests like lace bugs and azalea whiteflies. It´s very easy to burn up the fine roots. Fertilizing after late June in a northern climate promotes tender growth in the fall, which doesn't harden off before the first frosts of winter. This gets killed by the frost. This growth may have the buds for next year's flowers on it, which would also get killed by the frost. Research indicates that plants reasonably well supplied with nutrients, including nitrogen, are more resistant to low temperatures than those that are starved.

Do not fertilize at the time of planting, as this might injure the roots, but water deeply. Also, if newly purchased plants have little white BB-like balls in its container don't even think of fertilizing for a while. The little balls are fertilizer and those plants have been pushed to the hilt. Plant them as soon as possible and let them adjust. Plants that have been given a soil mixture rich in organic matter probably will not need feeding for several years. Do not stimulate fast growth because it produces long weak stems and few flowers. The National Arboretum warns: "Excess nutrients may promote larger than normal populations of azalea pests like lace bugs and azalea whiteflies. If your azalea foliage loses its deep green color, test your soil to make sure that the pH is not too high." But if a plant seems weak or sickly and the pH is not too high, use cottonseed meal or a special rhododendron-azalea-camellia-holly fertilizer such as Holly-tone dusted on the soil in early spring. Supplemental feeding later is not normally needed, but phosphorus and potassium may be applied any time.

What: Rhododendron guru Harold Greer <www.greergardens.com> wrote: "Oregon State University did extensive testing on peak fertilizer ratios for rhododendrons. They came out with a 10-6-4 formula. I have modified this a bit, and made it 20-12-8-8, the last 8 being sulfur. I also added some slow release nitrogen in the "20" of the mix. It has been a very successful mix for years, and is now sold to many people who swear by it. I have even sent bags of it to Alaska, where the cost of transportation is more than the cost of the fertilizer! Other mixes will work just as well, there is no one perfect secret fertilizer." Phosphate and potash do not disappear from the soil, but build up little by little with successive fertilizing. Therefore, the high phosphate formulas do not provide extra help to the plant.

Miracid (Miracle-Gro water soluable azalea & rhododendron fertilizer) can be more of a problem than a solution for outdoor plants. It is a 30-10-10 fertilizer. The 30 is nitrogen, which promotes foliage growth and inhibits flower bud production.

For acidity, flowers of (powdered) sulfur or iron sulfate are best. Do not use aluminum sulfate since aluminum builds up in the soil and is toxic to most plants eventually. For flower bud production and hardiness, super phosphate is best. Around the base of each plant I use a tablespoon of dry sulfur and a tablespoon of dry super phosphate when a plant shows signs of problems.

For a general fertilizer for rhododendrons and azaleas, Holly-tone is preferred by many growers. It is an organic 4-6-4 fertilizer with powdered sulfur, minor elements such as magnesium, iron and calcium, and trace elements also. (The Miracle-Gro pelatized slow-release azalea and rhododendron product is OK.) When fertilizing only fertilize once in the spring and at half the rate on the package. Some people fertilize once before blooming and once after blooming, but only fertilize at half the rate on the package.

Do not mistake the normal wilting action caused by extreme heat or cold as an indication of a problem. It is normal and will go away when milder temperatures return. Desiccation of the roots can be serious in cold or hot conditions. Watering may be needed in winter or summer.

The "rhododendron tonic" is a good formulation for rhododendron and azalea problems indicated by chlorosis.

Diane Pertson, Otter Point, Vancouver Island ,

wrote: I have found the following foolproof formula for chlorotic leaves or a rhododendron that isn't looking healthy:Purchase a bag of Epsom Salts crystals (magnesium sulfate) (available here in bulk at farm-and-feed outlets), about $4.00 for a 5 lb. bag - and a bottle of FULLY Chelated Iron & Zinc (this is a very concentrated liquid - the chelation means it is in a form that can be readily absorbed by the plant), about $7.00 for 1 quart; In a one gallon watering can, put in 2 Tbsp. of Epsom Salts crystals and 2 Tbsp. of Iron and Zinc liquid - fill with warm water and stir to dissolve; Sprinkle this over the rhododendron - by that I mean drench the leaves with the solution and pour the remainder around the drip line of the root ball.

In 1-2 weeks, the leaves should be nice and green. You could repeat the process at this time if the leaves aren't fully green.

This works even better if, a month before, you have sweetened the soil by sprinkling a little Dolomite Lime on the roots. Very acidic soil can prevent the roots from taking up nutrients. As many of my rhododendrons are planted in very acidic soil under a canopy of giant cedar trees, I find an application of Dolomite and a light topdressing of mushroom manure in late spring is all they need.

If soil is too acid, the symptoms can be the same. Very acidic soil can prevent the roots from taking up nutrients. In the western USA where many rhododendrons are planted in very acidic forest soil, an application of Dolomite and a light topdressing of mushroom manure in late spring is all they need. Sprinkle the lime on in late winter, very early spring. Don't overdo it - just a light sprinkle. If it is mid-spring, get the lime on right away so the rhododendron roots will be able to take up the soil nutrients in time for new growth. If you don't have rain, water it in well.

Vicki Molina in Portland, Oregon, reported after using coffee grinds from Starbucks Coffee House for about 18 months that Van Veen Nursery was very satisfied with the results. 1) it helps to aerate their clay soil. 2) slugs don't like to go through. (So you can see they have both mixed in and put on top.) It does help to make the soil more acidic. But it does not replace fertilizer.

They suspect that by making the soil more acidic you are actually helping the uptake of magnesium. This in turn helps iron uptake and that helps to make the plant green. So really you are starting a process not fertilizing. Combine the coffee with horse mature and organic mulch and watch the amount of fertilizer you use decrease dramatically. As for how they apply it, when the plant is dry and just before it rains they sprinkle it on and around. The rain takes it from there. Otherwise they incorporate into the new beds. No exact rate, just cover the top and work it in. (Courtesy of Vicki Molina) Return to Top

Nitrogen & Magnesium: Rhododendrons require nitrogen for general well being and especially for foliage and flower production. To use nitrogen a plant needs magnesium, so magnesium sulfate (Epsom salts) is often used in conjunction with nitrogen if the plants look pale green.

Phosphorus: Rhododendrons require phosphorus, as well as nitrogen, and adequate sunlight to produce flower buds. Not always understood is the length of time required for phosphorus to reach the root system and be taken up by the plant. As long as six months may be necessary for this process. Rhododendrons which have formed few, if any, flower buds by fall should receive an application of granular phosphate some time during the winter to assure flower bud development during the following summer months. High levels of phosphorus in the soil can lead to chlorosis.

Potassium & Iron: Potassium deficiency can be difficult to diagnose. A plant must have sufficient iron to utilize available potassium. For this reason the symptoms of potassium and iron deficiency are almost identical in the initial stages. Potassium deficiency begins with leaf yellowing, which eventually spreads between the veins. Leaf tips and margins show scorch and necrosis.

Iron: Lack of iron causes much the same symptoms as lack of magnesium, but with the younger leaves also showing yellowing between the veins. Iron deficiency is frequently caused by too high a soil pH, often the result of mortar or mortar building debris in the soil near the roots. A soil test should be performed to see whether high pH is a problem and if it is the soil should be acidified. For a quick but temporary solution, ferrous sulfate can be added to the soil or chelated iron can be sprayed on the foliage, but the pH should be corrected for long-term good growth.

Magnesium and calcium: A wide selection of the native species originating in Asia grow in mountains of dolomite limestone where the pH reading approximates 6.0. The addition of dolomite, which is a combination of magnesium carbonate and calcium carbonate, to our plantings darkens foliage color and increases flower buds. Gypsum, the common name for calcium sulfate, is another type of fertilizer some gardeners seem to have used successfully to improve the quality of their rhododendrons.

Calcium is also essential to good rhododendron growth. Calcium can be obtained either from gypsum or from agricultural lime. Gypsum will not raise soil pH, while lime will, therefore, lime is not generally recommended on acid loving plants such as rhododendrons and azaleas.

Trace Elements: In addition to the major elements, most gardeners are familiar with iron and magnesium deficiency, but all do not realize a rhododendron requires some, but often only a minute amount of boron, manganese, zinc, molybdenum, copper and possibly aluminum. Most of these elements are usually in the soil, but if not available, they could be the cause of poor rhododendron performance of some kind. Many of the more expensive fertilizers incorporate these trace elements.

Soil Testing: The more avid gardener should test his soil for deficiency or surplus of basic elements. Sometimes the soil of a particular location is known for excessive boron, for example, or for low phosphorus content. A further problem could be the water supply which might contain too much salt or some of the heavy metals. The zealous grower should concern himself with this potential problem.

Acidity: Most authoritative books and articles state that rhododendrons are acid lovers and that the pH of the soil should be between 4.0 and 4.5. The late rhododendron nurseryman Ted Van Veen reported that a pH of 5.5 to 6.5 was quite successful in his nursery in Portland, Oregon.

Mycorrhizae: The word "Mycorrhiza" is given to a mutualistic association between a fungus (Myco) and the roots (rhiza) of the plants. This association is a Symbiosis because the relationship between the organisms bring advantages for both species. The macrosymbiont (the plant) increase the exploration area in the soil with the intrincade net of hiphae that increase the uptake water and nutrients from the soil interphase. The microsymbiont (the fungus) use the carbon provided by the plant to its physiological functions.

Dr. Dirr of Arnold Arboretum reported: "The word mycorrhizae often surfaces in relation to ericaceous plants. There is little doubt that they play a prominent part in plant survival under low fertility situations. I have collected roots from Vaccinium corymbosum, highbush blueberry, in the wild and noted extensive mycorrhizal infections. However, plants (Rhododendron, Leucothoe, blueberries) grown under high nitrogen nutrition failed to show an infection. Mycorrhizae are fungi that live in symbiosis with plant roots to the mutual benefit of host plants and fungus."

Three major forms of Ericaceous mycorrhizae have been described:

Mycorrhizae are probably most important in mineralizing certain essential elements, especially phosphorous. It is obvious that plants can survive without mycorrhizae. You might dig one of your rhododendrons and examine the roots. If the young roots appear swollen or flattened then there is a good chance the roots are infected."

To Fertilize or Not To Fertilize ...

Rhododendron guru Harold Greer of Eugene, Oregon, gives the following advice. "Rhododendrons do require adequate nutrients to grow and flower at their best, and these nutrients are usually provided from some form of fertilizer. Whether you use organic or 'chemical' is your choice. Applied in proper amounts, either type will produce healthy plants. A properly fed plant is hardier and will withstand more cold than one that is under-fed. Research done by Dr. Robert Ticknor of Oregon State University indicates that more nitrogen is needed than what was once thought. He now recommends a 10-6-4 (nitrogen, phosphate, potash) formula. While phosphate does promote bud set, apparently the plant can only use a certain amount. Unlike nitrogen, phosphate and potash do not disappear from the soil, but build up little by little with successive fertilizing. Therefore, the old high phosphate formulas do not provide extra help to the plant. For most garden situations the old rule of "once before they bloom" and "once after they bloom" is still a sensible approach."

Rhododendrons and azaleas have a fine, hair-like root system, which grows outward on the top 2-3 inches of soil. Do not cultivate around the shallow roots of rhododendrons and azaleas. Cultivating the soil around rhododendrons and azaleas can damage their roots. Instead, keep the roots cool and moist with a permanent 2- to 3-inch mulch of wood chips, oak leaves, pine needles, pine bark or other light airy organic material to conserve moisture and discourage weeds. Keep the mulch from touching the trunk.

Because azaleas are shallow-rooted, they are among the first plants in the landscape to show moisture stress. This is why a good mulch layer is very important. Watering is a critical element in growing rhododendrons and azaleas. Many rhododendrons have been killed by overwatering in sites where drainage was poor. If the soil is moist but the plant still wilts, mist over the plant lightly to increase humidity. This practice is especially important for newly planted evergreen species. Avoid excessive irrigation in fall. Plants kept dry in September will tend to harden off and be better prepared for the winter. If the fall has been excessively dry, watering should be done after the first killing frost. At that time watering will not reduce winter hardiness but will prepare the plant for winter. The soil should be thoroughly moist before cold weather sets in. The best time for fall watering is about Thanksgiving.

Too much water can cause Phytophthora crown rot or wilt. This root rot is the major killer of rhododendrons and azaleas. It develops when roots are growing in wet conditions. Plants infected with crown rot caused by the oomycete, or water mold, Phytophthora have roots which become clogged with brown oomycete, or water mold, internally. The roots get blocked and the plant wilts and dies. There is not much of any cure for crown rot. Some varieties of rhododendrons are vulnerable (Chionoides, Catawbiense Album, Nova Zembla) and some are resistant (Roseum Elegans, Scintillation, PJM). Sphagnum moss and bark dust combined with good drainage seem to prevent crown rot, but do not cure it.

Too little water can permit desiccation and also cause the plant to die. In less severe cases, drought has been observed to prevent flower buds from opening, as shown in photo on right, or causing open flowers to wilt prematurely. Usually watering is safer in cooler weather. In hot weather, moist roots can quickly progress into root rot. The best compromise is to 1) use a well-drained soil to prevent excessive moisture, 2) use a mulch to keep the soil cool and moist, and 3) only water after soil has started to become deficient in moisture. You can usually sense this when the leaves roll and only unroll at night. However this same condition occurs when the plant contracts root rot. [Photo courtesy of Harold Greer]

Too little water can permit desiccation and also cause the plant to die. In less severe cases, drought has been observed to prevent flower buds from opening, as shown in photo on right, or causing open flowers to wilt prematurely. Usually watering is safer in cooler weather. In hot weather, moist roots can quickly progress into root rot. The best compromise is to 1) use a well-drained soil to prevent excessive moisture, 2) use a mulch to keep the soil cool and moist, and 3) only water after soil has started to become deficient in moisture. You can usually sense this when the leaves roll and only unroll at night. However this same condition occurs when the plant contracts root rot. [Photo courtesy of Harold Greer]

Wilting: Do not mistake the normal wilting action caused by extreme heat or cold as an indication of a problem. It is normal and will go away when milder temperatures return. Desiccation of the roots can be serious in cold or hot conditions. Only water when necessary and in hot weather always err on the dry side, but don't hesitate to water plants that look wilted in the morning. In hot weather it is normal for rhododendrons to look slightly wilted in the heat of the day, but if they look wilted in the morning, then they are too dry. Watering may be needed in winter or summer. The photo on the left shows foliage damage to new growth from a drought. [Photo courtesy of Harold Greer]

When transplanting watering is much more critical since the root structure is usually compromised and is less capable of supporting a large mass of leaves. That is one reason that transplanting is more successful when the plant is dormant in cold weather.

Rhododendrons and azaleas have a fine, hair-like root system which grows outward on the top 2-3 inches of soil. Since the roots are so shallow, any cultivating or pulling roots out will disturb the roots. They like moist, but well drained soil with lots of organic matter and a good dressing of mulch. Soil around the rhododendron's shallow roots must be kept cool. To keep the soil weed free, cool and moist, mulch it with a 2-3 inch layer of an airy organic material such as shredded leaves, leaf mold, pine needles, or pine bark mulch. Don't use shredded hardwood mulch since it often drives the pH upward. Pine bark is especially useful since it can lower the pH where it is too high, but it is best used on relatively flat ground since it's light in weight and tends to float away in heavy rain. [Sketch courtesy of Harold Greer]

Rhododendrons and azaleas have a fine, hair-like root system which grows outward on the top 2-3 inches of soil. Since the roots are so shallow, any cultivating or pulling roots out will disturb the roots. They like moist, but well drained soil with lots of organic matter and a good dressing of mulch. Soil around the rhododendron's shallow roots must be kept cool. To keep the soil weed free, cool and moist, mulch it with a 2-3 inch layer of an airy organic material such as shredded leaves, leaf mold, pine needles, or pine bark mulch. Don't use shredded hardwood mulch since it often drives the pH upward. Pine bark is especially useful since it can lower the pH where it is too high, but it is best used on relatively flat ground since it's light in weight and tends to float away in heavy rain. [Sketch courtesy of Harold Greer]

Rhododendrons do best when they have about a 2" to 3" layer of mulch to hold in moisture, prevent weeds, and keep the roots cool. Since most mulches are organic, they need to be topped off periodically, usually about every year or two. Do not make the mulch over 3" thick. Keep the mulch about 2" to 3" back from the trunk/stem of the plants to avoid bark split and rodent damage. It is best to mulch with a 2-inch layer of an airy organic material such as wood chips, ground bark, pine needles, pine bark or rotted oak leaves. A year-round mulch will also provide natural nutrients and will help keep the soil cool and moist.

Also, in the winter such a layer protects the roots from freezing and thawing cycles which cause heaving. Keep the mulch from touching the trunk to avoid bark split, fungus and rodent damage. One common misconception is that peat moss is a mulch. It is not. In fact when one uses peat moss as a mulch, it wicks moisture out of the soil rather than holding moisture in the soil which is the normal function of a mulch. Peat moss is a soil amendment to be used when preparing the soil in a bed and can cause severe problems when used as a mulch including preventing moisture from reaching the soil. It also tends to blow around.

Mulching is a simple yet beneficial cultural practice for azaleas. Mulches conserve water in the soil, insulate roots against summer heat and winter cold, and discourage weeds. Replenish mulches annually, as needed, to maintain a 3- to 5-inch layer on the soil surface. Fine-textured organic mulches such as pine straw or shredded bark are best. Fall leaves are an excellent mulch.

Avoid cocoa shell mulch. It harms rhododendrons and azaleas. It blows away in strong winds. If floats away in heavy rains. It can kill a dog, not common but has happened. Cocoa shells have a high potassium content that injures plants such as maples, lilacs, rhododendrons, and azaleas.

The roots of Black Walnut (Juglans nigra L.) and Butternut (Juglans cinerea L.) produce a substance known as juglone (5-hydroxy-alphanapthaquinone). Persian (English or Carpathian) walnut trees are sometimes grafted onto black walnut rootstocks. Many plants such as tomato, potato, blackberry, blueberry, azalea, mountain laurel, rhododendron, red pine and apple may be injured or killed within one to two months of growth within the root zone of these trees. The toxic zone from a mature tree occurs on average in a 50 to 60 foot radius from the trunk, but can be up to 80 feet. The area affected extends outward each year as a tree enlarges. Young trees two to eight feet high can have a root diameter twice the height of the top of the tree, with susceptible plants dead within the root zone and dying at the margins. The juglone toxin occurs in the leaves, bark and wood of walnut, but these contain lower concentrations than in the roots. Juglone is poorly soluble in water and does not move very far in the soil. [From Ohio State University Extension Fact Sheet HYG-1148-93 by Richard C. Funt and Jane Martin]

The Ohio State University Extension and the American Horticultural Society have reported that R. periclymenoides, formerly R. nudiflorum, Pinxterbloom Azalea, and Exbury Azaleas Gibraltar and Balzac will grow near Black Walnut and Butternut trees. They also list many other plants that will grow in the root zone of these trees.

Unfortunate for us and fortunate for deer, conditions are favoring the explosion of the deer population. Deer are becoming a problem even in urban areas. They are threatening their own habitat. Depending upon the deer pressure in your area, you response will vary. Where deer are just casual visitors, usually a number of deer repellents will work. They only work for a while, so it is best to rotate them. Some repellents used are: eggs, human hair, soap, feathermeal, bloodmeal, creosote, mothballs, tankage and commercial chemical repellents. The greatest amount of protection for home gardens with repellents is obtained by using several different repellents and rotating their use. Repellents should be applied before damage is likely to occur and before deer become accustomed to feeding on the plants.

Rhododendrons with a heavy indumentum (fuzz on the underside of the leaves) are not popular with deer and are usually not bothered. Some of the cultivars known as "Yaks" have this indumentum. Among the most popular plants are 'Mist Maiden' and 'Ken Janek.' There have been many sprays to deter deer and they all worked for a while, usually until the deer became hungry. They all were temporary and had to be reapplied after every rain, or every couple weeks when it didn't rain. A Swedish product has the promise of deterring deer for up to 6 months. Tests have shown that it causes about a 95% reduction in deer damage. The product is Plantskydd Deer Repellent.

The following home remedies (Table 1) and commercial chemicals (Table 2) repel deer.

Table 1. Noncommercial Deer Repellents (Home Remedies)

| Repellent | Type | Application |

| Egg spray | Odor | A whisked egg to a gallon of water. Must be reapplied every 2 or 3 week and after rain. This has been successful for many people in Pennsylvania. |

| Milorganite | Odor | This is sewage plant sludge from Milwaukee, WI. It is safe and sold as a 6-2-0 fertilizer. When used around rhododendron beds at half the normal rate for turf, it deters deer from the area. It must be applied monthly and after heavy rain storms and each snowfall. |

| Human Hair in Bags | Odor | Collect male hair from local barbershop. Put two large handfuls of hair in open mesh bag. Hang bags near crops 28-32 inches above ground every 3 feet. |

| Tankage in Bags | Odor | Put 1/2-1 cup of tankage (animal waste) in cloth bag. Hang bags in same manner as hair. |

| Bars of Soap | Odor | Brand makes no difference. Use small bars or cut large ones in sections. Hang by wire in same manner as hair. |

| Published in Audubon Magazine | Odor | Half-cup of whole milk whisked together with one egg and combined with a tablespoon each of cooking oil and lemon-scented dish detergent, diluted in one gallon of water. For a more potent brew, he spices it up with a couple of drops of rosemary oil and a dash or two of hot sauce. This mix should be applied to plant leaves with a spray bottle every 10 to 12 days, and in spring it can be combined with fish emulsion for fertilizer. |

Table 2. Commercial Deer Repellents (Follow Manufacturer Labels)

| Repellent | Type | Distributor/Manufacturer |

| Bobbex | Odor, Taste | BOBBEX, Inc., 52 Hattertown Rd., Newtown, CT 06470, 800-792-4449, http://www.bobbex.com/ |

| Bonide Shot Gun Deer Repellent | Taste | Bonide Chemical Co., Inc. 2 Wurz Ave. Yorkville, NY 13495 (315)736-8231 or 800-424-9300, http://www.bonideproducts.com/ |

| Chaperone Rabbit and Deer Repellent | Taste | Sudbury Laboratory, Inc. 572 Dutton Rd., Sudbury, MA 01776 |

| Deer Scram | Odor | Enviro Protection Industries Company Inc., 27 Link Drive, Suite C, Binghamton, NY 13904 or 877-337-2726 or http://www.deerscram.com |

| Hinder Deer and Rabbit Repellent | Taste | Pace International, LP, 500 7th Avenue S, Kirkland, WA 98083 |

| Nott's Chew Not | Taste | Nott Manufacturing Co., Inc. P.O. Box 685 Pleasant Valley, NY 12569 (914)635-3243 or Mellinger Co. N. Lima, OH 800-321-7444, http://www.nottproducts.com/ |

| Deer-Away Big Game Repellent | Taste | IntAgra, Inc. 8500 Pillsbury Av. S. Minneapolis, MN 55420 (612)881-5535 or 800-468-2472 |

| Deer Off | Taste | Deer Off 800-800-1819 http://www.deeroff.com |

| Deerbuster | Taste | Deerbuster 9735 A Bethel Rd., Frederick, MD 21702-2017 800-248-3337 http://www.deerbusters.com |

| Deer Solution | Odor, Taste | Natural Pest Control or Natrual Pest Control. [Spelled both ways???] [A website with a similar name is selling a recipe for $35.] |

| Deer Stopper | Odor, Taste | Messina Wildlife Management, P.O. Box 122, Chester, NJ 07930 |

| Liquid Fence Deer & Rabbit Repellent | Odor | The Liquid Fence Co., P.O. Box 300, Brodheadsville, PA 18322, 1-800-923-3623, http://www.liquidfence.com/ |

| Millers Hot Sauce Game Repellent | Taste | Miller Chemical Box 333 Hanover, PA 17331, http://www.millerchemical.com/ |

| N.I.M.B.Y. | Taste | DMX Industries 6540 Martin Luther King St. Louis, MO 63133 (314)385-0076 |

| Not Tonight Deer | Taste | Not Tonight Deer Box 71 Mendocino, CA 35460 (415)255-9498 or http://www.nottonight.com |

| Plantskydd | Taste, Odor | 4413 N.E. 14th St. PO Box 4821, Des Moines, IA 50306, 800-252-6051. This is reported as a long lasting repellent. http://www.plantskydd.com/ |

| Tree Guard | Taste | Nortech Forest Technologies, Inc. 7600 W27th St., #B-11 St. Louis Park, MN 55426 (612)922-2520 or 800-323-3396 |

To keep deer from becoming acclimated to a particular repellent, frequently switch to different ones. The most effective method is deer fencing. After that, the egg spray seems to be next best. The most popular comercial products are Deer Solution, Liquid Fence, Deer Stopper, Deer Off, Bobbex and Hinder. Liquid Fence seems to be the most popular commercial product. All methods are enhanced if one also uses Milorganite.

Since 1994 I have had to prevent deer damage. Deer love to eat green leaves and needles; when snow is on the ground our shrubs are the greenest thing around. They do avoid spruce, but they eat most everything else including rhododendrons and azaleas.

If you have had winter deer damage, just make sure that in the spring the plants have good culture, making sure they are not suffering from chlorosis or any other problems. I might add a little Holly-tone but nothing stronger. I need to use super phosphate since my soil is phosphorus deficient and phosphorus is vital to the well being of the plants. I add sulfur near buildings since my soil tends to loose its acidity near masonry walls which leach lime into the soil, even after 185 years.

Deer Netting: To prevent winter deer damage you need to take prompt action in the fall and subsequent falls to insure it doesn't happen again. I use a product found in hardware stores called deer netting. It is similar to bird netting but heavier and courser. I wrap groups of plants together and wrap isolated plants individually. I fasten it on with tie wraps or twine and just cut the tie wraps or twine off in the spring. The important thing is to take deer netting off in the spring before the rhododendrons and azaleas sprout and grow through it. If the foliage does grow through the netting, the netting is hard to remove without damaging the plants. The course deer netting is good in that it doesn't get covered with snow unless it is a very wet snow. Otherwise the snow just goes through it.

Deer Fencing: A heavier product is deer fencing. I have a couple beds of azaleas that were decimated during the summer before I used deer fencing. It is typically 7' to 8' tall and can be wire mesh or a heavy plastic mesh. I purchased the heavy plastic mesh deer fencing with easy to install steel posts from: http://www.deerxlandscape.com/cgi-bin/webc.cgi/Fencing.html

When using deer netting in an area that is heavily traveled by deer, place something visible like plastic grocery bags on the netting so the deer can see it and avoid it. Soon they will change their travel path and it won't be a problem. However, if a new fence or deer netting is place across their natural path, they will do almost anything to get through. Persist until you get them to change their travel path. One interesting side effect is that squirrels don't see deer netting too well and bounce off it like a trampoline. They soon learn to watch out for it.

Research by various state horticulture departments shows that the typical deer resistance of rhododendrons and azaleas is:

| Plants Rarely Damaged: |

|

| Plants Seldom Damaged: |

|

| Plants Occasionally Damaged: |

|

| Plants Frequently Damaged: |

|

When: The best time to prune azaleas is right after they finish blooming. As with most spring bloomers, rhododendrons start to form the next year's flower buds in mid summer and by fall the buds are fairly well developed. Pruning after mid summer removes the next year's flower buds. Do not pinch after June because then flower buds will not have time to develop for the following year.

Deadheading: For maximum flower production, pinch off faded flowers or the developing seed capsules that follow [deadheading]. Most successful rhododendron gardeners do not deadhead. It is not because they don't believe in it or that they don't want to do it, but rather because they have so many plants and so many other more important tasks that they don't have time to do it. Does this cause a problem? Not really. Some plants that are reluctant to bloom or have disease problems such as petal blight or in an area that is marginal for the plant in question may benefit from deadheading, but that is unusual.

How: Pruning is seldom needed except for removal of faded flowers, but if it is needed, branches may be trimmed immediately after flowering. There is little need for pruning azaleas and rhododendrons. If growth becomes excessive, reduce the size with light pruning. Azaleas sometimes branch poorly and form a loose, open shrub. Plant form can be improved by pinching out the soft, new shoots of vigorous-growing plants. It is best to prune within two weeks of when they stop blooming. This is to prevent removing next year's flower buds. Rhododendrons and azaleas may be pruned after the flowers have faded to induce new growth. Prune out dead, diseased or damaged branches, and in cases where plants have become scraggly, start cutting the oldest branches back to encourage growth in younger branches. Pruning in the fall is not recommended since it will remove the buds for next year's flowers.

With the larger leaved rhododendrons (elepidotes), you must prune just above growth joints. Each year as the plant starts to grow there is a visible point where the plant started growth. We call this point a growth joint. Prune just above this point, because that is where the dormant growth buds are located. Don't prune between joints, because there are no dormant growth buds in that area. However, with azaleas and the small leafed rhododendrons (lepidotes), you may prune anywhere along the stem, though you may not be able to see them, these plants have dormant growth buds nearly everywhere.

As a plant grows, some of the inside limbs will be shaded out and become weak and die. It is a good idea to remove these, plus other weak limbs that are on the ground or crossing over each other. This provides better air circulation and does not provide a place for insects and diseases to start. Check azaleas for wilting or dead branches in late summer that may be the result of fungal cankers. These branches should be pruned back to clean white wood that is not infected while the weather is dry to prevent the spread of diseases.

Azaleas: Evergreen azaleas can be sheared for hedges or borders. Unlike rhododendrons, evergreen azaleas can be sheared each year after flowering to create a dense rounded plant. This is done extensively and with great results by highly trained Japanese gardeners. Deciduous azaleas can be cut anywhere on the stem and they will branch from that point, though they should not be sheared as severely as evergreen azaleas. After pruning, spraying with a fungicide may prevent infection.

A little Rhododendron/Azalea trivia: One Rhododendron blooms on new growth after it sprouts in the spring. It is Rhododendron camtshaticum. It is a small deciduous species that grows in the Bering Straits of Alaska and on the northern islands of Japan. It has rosy plum flowers and has at least one rare white form.

Pinching: A friend of mine has the most beautiful rhododendron and azalea garden. All plants are about waist height. From any place in the garden you can see just about every plant. During the flowering season it is awesome. I asked him how he keeps the plants so well kept and his reply was that he just removes the top foliage buds each year with his fingers in the late fall or early spring. This can be done once the rhododendrons reach the height you want. Then each spring after the flower buds start to swell and the smaller leaf buds are obvious, break off leaf buds [pinching] on the top of the plant to prevent it from growing taller. You must be careful not to damage any flower buds. No pruning at all. This technique minimizes disease and insect damage. It works very well for him. It is labor intensive, but well worth the effort.

Severe Pruning: If necessary, you can remove a great deal of material. It is a general rule to not remove over 1/3 of the leaf area each year. Pruning is generally used to control unsatisfactory height or width of a plant. I don't prune very often and try to limit pruning to plants which have a shape that is unsatisfactory or dead branches. If I want to cut trusses for bouquets, I always cut the tallest flowers since this helps keep the plant within bounds.

Severe pruning is not uncommon with rhododendrons and azaleas. A healthy plant can be cut to the ground and will usually come back. Rhododendrons and azaleas have dormant buds beneath the bark which sprout to form new growth after severe pruning. However, Richard Colbert reported that such attempts at Tyler Arboretum were only successful if the plant had enough sun light. Those in heavy shade frequently died. He recommend first opening up the shade by thinning the forest canopy. Then he recommends just removing some of the top to induce new growth at the base. Then when that new growth is established, the remainder of the top can be removed.