Editorials Concerning

Rhododendrons and Azaleas

Yes, Virginia, Rhododendrons are Invasive

The New York Sun ran the headline in 1897, “Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus.” Some rhododendron lovers may be just as surprised to hear that in various parts of the world, certain rhododendrons are invasive. The Global Invasive Species Database lists Rhododendron ponticum.

It lists the native range as:

Rhododendron ponticum displays a disjunct native distribution, with R. ponticum ssp. baeticum found in south-west Spain and southern Portugal, and R. ponticum ssp. ponticum found in Turkey, Lebanon, Bulgaria and the Caucasus (Hulme, 2006).

It lists the introduced range as:

Rhododendron ponticum is known to have naturalized in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Belgium, France and Netherlands with an increasing invasion trend in continental Europe. It is also reported to be naturalized in New Zealand (USDA-ARS, 2010) and present in Austria (Hulme, 2006).

The British Forestry Commission has done an excellent job of tracing how this problem came about at. They give this history:

Rhododendron ponticum was introduced into the British Isles around 1763 as a cultivated flowering plant and was widely planted in gardens, parks and estates. It was also planted extensively in Victorian hunting estates, particularly in western coastal areas, under woodland canopies and on heathland areas to provide shelter for game species. It was later used as a rootstock for less hardy scions of Rhododendron species and cultivars, but the original rhododendron rootstock often produced its own shoots, which out-competed and then replaced the species or cultivar and reverted back to wild type rhododendron.

During its cultivation and use as a rootstock, rhododendron was crossed with several other Rhododendron species to produce a range of hybrids called the ‘iron-clads’ or Hardy Hybrids. These hybrid plants were further used in cultivation and plantings. The severely cold winter of 1879–80 killed many evergreen plants, including Rhododendron species, being planted at that time and only some of the hybrids appear to have survived.

These surviving hybrid bushes produced viable seed and enterprising gardeners collected their seedlings for distribution around the country.

DNA analyses of naturalized ‘wild’ rhododendrons indicate that most of the naturalized

bushes in the British Isles are derived from material originally introduced from the Iberian Peninsula. A smaller proportion has been shown to come from Turkish material. They also suggest that most of the naturalized material in the British Isles shows signs of introgression with other rhododendron species, particularly R. maximum and R. catawbiense. This is especially noteworthy for the eastern Scottish populations of rhododendron, which have had a high introgression rate with R. catawbiense, which may confer improved cold tolerance. The altered gene pool thus created would increase the competitiveness of rhododendron in Britain, everything else being equal.

They go on to say,

R. ponticum and its hybrids are aggressive colonizers that reduce the biodiversity value of a site; obstruct the regeneration of woodlands and once established are difficult and costly to eradicate. As bushes mature and occupation of an invaded site increases, physical access can be reduced by the sheer density and size of the plants present, and the cost of some management operations (e.g. felling) can increase if the bushes require treatment first. Mature bushes also act as a prolific seed source for invasion of adjacent areas, and are a continued source of new plant material into areas successfully cleared.

The global Invasive Species Specialist Group, who maintain the Global Invasive Species Database has put together a guide for eradicating Rhododendron ponticum, in case you should need some advice.

So, in our gardens, rhododendrons are robust. In areas where they are not wanted, they are invasive.

Return to Top

Debunking the Myth that Rhododendrons are Allelopathic

Some plants are allelopathic, that is the plants produce toxins to prevent competition from other plants such as what black walnuts and some Eucalyptus do. There are British myths that claim that Rhododendron ponticum has become invasive in Britain because it is allelopathic. R. ponticum is invasive in the UK, but it is not allelopathic. One researcher, James Merryweather, has searched the literature and debunks that myth:

There seems to be no good reason for us to understand from the scientific literature (of which there is little) that R. maximum has a chemical allelopathic (poisoning) inhibitory (or fatal) effect upon plants which might attempt to grow under its light-limiting canopy. There is absolutely no reason to consider that R. ponticum, to which no similar research has been applied, has an equivalent effect. If such an effect had been demonstrated with R. maximum, it would it be reasonable to speculate that similar effects might also apply to the admittedly very closely related R. ponticum, and conclusions contrived only after research had provided corroborative data. None of these conditions prevails.

Unless evidence that contradicts current knowledge is forthcoming we must consider that eviction of native floras by either species of Rhododendron is caused mainly by shading, and perhaps some other less potent factors, whilst the role of allelopathy can be considered, at best, negligible.

Post rhododendron, a site is inhospitable due to soil/litter modification by rhododendron plus soil biota impoverishment caused by exclusion of plants and establishment of a monoculture, so that restoration of the original plant community will be distressingly slow. To the under informed or misconception driven observer such a site will have the appearance of a place that has been poisoned.

It is my contention that "Rhododendron poisons the soil" is a case of the memetic evolution of a cautious observation into dogmatic factoid. Lots of people have believed and iterated the dogma, but few if any have questioned it or looked for alternative explanations.

He goes on to approve of the "Lever and Mulch" eradication of R. ponticum. He then points out that after R. ponticum is eradicated, the soil is perfectly fine for a wide variety of other plants, further casting doubt on any possibility of allelopathic effects.

Return to Top

Debunking the Myth that Rhododendrons Originated in SE Asia

Fossil records indicate the Ericaceae emerged about 68 million years ago. Rhododendrons were found in fossils in North America and Eurasia. Rhododendrons have been in existence for at least 55 million years, but not before 68 million years ago. This is significant because the regions of north Burma, southwest China, and New Guinea that we think of as the centers of rhododendron diversity did not exist 55 million years ago.

One of the most spectacular events in Earth's history is the long drawn-out collision of India with Asia which began about 40 million years ago and continues today. This collision set in motion the chain of events which lead to the creation of the high mountain regions of SE Asia and to conditions highly favorable to the development of a rich rhododendron flora.

The most recent estimates are that the rapid uplift began about 20 million years ago, and that the plateau reached approximately its present elevation about 8 million years ago. The assembly of a landmass as large as Asia and the uplift of the Himalayas and Tibet profoundly affected climate. The formation of high mountains influced not only the topology but also the climate.

After Rhododendrons originated over 55 million years ago, they were more-or-less continuously distributed across North America and Eurasia. The climate was mild and change was slow. Their range became much reduced as a result of worsening of the global climate caused by the formation of high mountains. This worsening began about 25 million years ago, was clearly marked by about 15 million years ago, and became extreme with the onset of the current glacial period about 3 million years ago.

Small founder populations of the sub-genera Hymenanthes and Rhododendron (but not azaleas) situated marginal to their main range were able to enter and retain a foothold in the newly developing high mountain regions on the southeastern fringe of the Tibet-Himalayan region. It was from there that the vireyas spread into the mountains of the high-island archipelago. By taking advantage of special newly developing conditions, these small, originally peripheral populations have become now the most numerous and diverse.

The place of origin of rhododendrons is not known, but it was not the high mountain regions of SE Asia where nowadays they are most diverse and abundant. That region did not exist then. These conclusions are based on the fossil record of rhododendrons and are based upon the observations of many scientists. They provide reasonable explanations of the present remarkable distribution of rhododendrons and of their differing abilities to cross and recross.

Ref: Why Rhododendrons grow where they do and how they got there.

Return to Top

Don't Use Aluminum Sulfate on Rhododendron & Azaleas

Aluminum sulfate will change the soil pH instantly because the aluminum produces the acidity as soon as it dissolves in the soil. However aluminum sulfate should be reserved for use only with hydrangeas to promote blue flowers. Aluminum is necessary for the flower color change in hydrangeas but can cause aluminum toxicity in other plants such as blueberries, rhododendrons and azaleas. Many acres of land in the world are unusable for crops due to soil acidity and aluminum toxicity. Simply lowering the soil pH with any product will help hydrangeas flowers to be blue but the competitive deep blue will require aluminum sulfate additions.

If you Google "extension aluminum sulfate rhododendron azalea" you will find some extension agents still recommending aluminum sulfate while most are warning against using it. It is sad that such bad advice is still being given.

Never use aluminum sulfate for making the planting medium for rhododendrons and azaleas more acid. Thousands of rhododendrons and azaleas are killed each year by the addition of aluminum sulfate to planting mediums. Aluminum ions under very acid conditions are very toxic to all of the rhododendron genus and many other plants.

Aluminum is not considered to be an essential element for plant growth. In fact, for most plants, high levels of available soil aluminum are toxic causing stunting of root growth and eventual death if soil aluminum is high enough. Usually the soil pH has to be less than 4.5 for this to happen. Rhododendrons and azaleas are more vulnerable than many other plants.

Although aluminum sulfate often is recommended to gardeners for increasing the acidity of the soil, it has a toxic salt effect on the roots of plants if it is used in large amounts. Small amounts do not cause much of an effect. About 7 lb. of aluminum sulfate are required to accomplish the same effects as 1 lb. of sulfur.

The one area where aluminum sulfate is recommended is in making blue hydrangeas blue. The chemistry of hydrangeas is such that not only acidity is necessary, but also aluminum ions are also necessary to make the flowers blue due to the aluminum binding with the anthocyanin. Hence, blue hydrangeas shouldn't share the same beds with rhododendrons and azaleas. Over application of aluminum sulfate can even be toxic to hydrangeas.

I am sure that part of the reason for the bad advice is that aluminum sulfate is very quick in modifying the soil pH. Sulfur is very slow, but is much more effective eventually.

Guy Nearing was one of the first to realize that aluminum sulfate was detrimental to rhododendrons and azaleas. His findings were published in the Journal of the ARS in 1955.

Rhododendrons are Vanishing by Guy Nearing

Today, the effect is thoroughly understood. The most eloquent article on adjusting soil pH for rhododendrons and azaleas was written by Sandra Mason with the University of Illinois, Champaign, slmason@uiuc.edu.

How to Lower Soil pH (and how not)

In her words, "Many acres of land in the world are unusable for crops due to soil acidity and aluminum toxicity."

Jump to Adjusting Soil pH

Return to Top

Open Up The Roots Before Planting

There are two all-too-common problems when planting.

1. Planting a dry root-ball.

2. Planting a plant from a container with the roots still circling around the root-ball.

Harold Greer probably explained the first point best:

Quite often a plant will get completely dry and then no matter how much water you apply, the root-ball will just keep shedding it. The top of the soil may seem wet, and the soil around the plant may even be very wet, but the actual rootball of the plant is bone dry. This is especially true for newly planted rhododendrons, and it is the major reason for failure, or at least less than great success with that new plant. It is hard to believe that a plant can be within mere inches of a sprinkler that has been running for hours and still be dry, yet it can be SO TRUE!

The second point is more commonly pointed out. When you take a plant out of a pot, usually there are many roots that are circling the rootball around the outside. If planted this way, those roots grow and form a hangman's noose around the entire root structure. That plant is certain to die eventually.

Fortunately both problems are prevented by proper planting. OPEN UP THE ROOTS!

It is necessary to remove the plant from the container and examine their roots. If the plant appears pot-bound and has a thick, dense mat of fibrous roots along the surface of the rootball, use a knife to make vertical cuts about every 2 inches and about 2 inches deep, equally spaced around the sides of the rootball. Then use your hands to gently loosen the roots where cuts were made and pull the roots outward. This process stimulates new root growth and allows water and nutrients to penetrate into the root mass. If the roots are not pot-bound, it is not necessary to slice them with a knife, but still loosen and pull the roots outward with your hands. When working with roots keep them moistened. Any roots that dry out will die.

If the plant has been transplanted several times it may be necessary to remove all soil so that previous areas that were pot bound in side the rootball when it was planted in smaller containers may be exposed. All roots must be separated so they go out from the center and do not circle. Those that cannot be straightened must be cut. If allowed to circle other roots, they will strangle the other roots as they grow larger. When working with bare roots of a plant, keep them moistened. Any roots that dry out will die.

Al Fitzburg recommends taking "a small rake type hand trowel and pull apart the rootball until the roots are open at the periphery of the ball."

|

| Remove from pot. Lay on side. Make deep X cuts in from side & bottom. |

|

Loosen the roots. Spread quarters.

|

|

Build a mound. Spread roots.

Plant 1 - 2” above grade. |

From Rare Find Nursery's excellent Planting Guide

Very important! Ericaceous plants such as rhododendrons and azaleas have fibrous roots and can become pot-bound (that is, the roots become matted around the edges of the pot they're grown in). So it is critical to scratch and roughen up the matted rootball to loosen the roots so water can penetrate and roots can grow into the surrounding soil. Use a small hand tool because doing it by hand is inadequate. DO NOT BE TIMID! You will hurt the plant far more by being too 'NICE' to it. A postmortem of dead plants often reveals that the roots were never disturbed before planting.

You can also 'butterfly' or quarter the rootball and spread the roots as near to horizontal as possible. Build a mound in the center of the hole and spread the roots over it. For non-ericaceous plants (most woody trees and shrubs) the roots should be loosened and spread out as much as possible, to allow the roots to penetrate into the surrounding soil. Be gentle when handling roots that are fleshy or brittle, such as magnolias. Cleanly cut off broken roots and any roots that grow backwards toward — or around — the trunk to avoid having them girdle the plant.

Place the plant in the hole and fill the hole with water. Let the water drain away. If it drains away quickly and the soil seems very dry, repeat. Backfill (replace soil around plant) AFTER the water has drained away and settle the soil around the roots. With some of the extra soil, make a saucer to retain water around the plant.

This assures that the rootball is not dry. The rootball has been opened up and soaked with water. At least now the plant has a chance. A plant with a dry rootball or circling roots has no chance.

Jump to How To Plant Rhododendron & Azaleas

Return to Top

Why is my rhododendron or azalea dying?

I am often asked what is killing my rhododendron or azalea. Of course I would have to be psychic and equipped with a microscope and other laboratory equipment to do a proper diagnosis, but, short of that, I can fall back on generalities about what rhododendrons and azaleas need and what they often don’t get. So here goes a one size fits all explanation:

First, it helps to be able to tell when a branch is dead. If there is no green cambium layer under the bark, then that branch is dead and it is best to prune such branches off. Even if there are no green leaves but there is a green cambium layer under the bark, the branch is alive. Such branches have dormant buds that may open and produce leaves in the future. One can look for the green cambium layer by scratching with their fingernail, or while cutting off the dead branches.

Drainage and Mulching

The chief cause of rhododendron death is water, either too much or not enough. Too much causes root rot which is terminal. Too little causes dieback which kills the plant one branch at a time. Rhododendrons and most other plants like "moist well-drained soil". That makes it sound like no matter what you do you can't do it right. However, if the area has good drainage and you use mulch, it should be easy to achieve moist well-drained soil. To check for good drainage, dig a hole about 10 to 12 inches deep and fill it with water. Then after it drains, fill it again and see how long it takes to drain. If the hole drains within an hour you have good drainage. If the water has not drained out of the hole within one hour, the soil is poorly drained and you must correct the drainage problem before planting. Install a perforated pipe or drain tile in the garden, making sure that the outlet is lower than the bottom of the planting hole, or build raised beds. [The sketch by Harold Greer shows how to use a raised bed.]  Rhododendrons are easy to transplant most any time. It is best to avoid transplanting when new leaves are coming out or the ground is frozen. If the drainage is OK, then you can keep the area moist with a good mulch layer. Mulches conserve water in the soil, insulate roots against summer heat and winter cold, and discourage weeds. Replenish mulches annually, as needed, to maintain a 3- to 5-inch layer on the soil surface. Fine-textured organic mulches such as pine straw or shredded bark are best. Fall leaves are an excellent mulch, except don’t use black walnut or butternut leaves. They have a chemical, juglone, that kills rhododendrons and azaleas. During hot dry weather, it is common to see rhododendron leaves look wilted. It they look wilted in the heat of the day, that is normal. If they look wilted in the morning, that is a sign that the plant is either too dry or dying from being too wet. It should be easy to tell which, but don't assume, check the soil with your finger. During drought periods, it may be necessary to water once in a while. A deep watering once or twice a week is much better than frequent watering. Only water when the plants show signs of being dry. Rhododendrons are easy to transplant most any time. It is best to avoid transplanting when new leaves are coming out or the ground is frozen. If the drainage is OK, then you can keep the area moist with a good mulch layer. Mulches conserve water in the soil, insulate roots against summer heat and winter cold, and discourage weeds. Replenish mulches annually, as needed, to maintain a 3- to 5-inch layer on the soil surface. Fine-textured organic mulches such as pine straw or shredded bark are best. Fall leaves are an excellent mulch, except don’t use black walnut or butternut leaves. They have a chemical, juglone, that kills rhododendrons and azaleas. During hot dry weather, it is common to see rhododendron leaves look wilted. It they look wilted in the heat of the day, that is normal. If they look wilted in the morning, that is a sign that the plant is either too dry or dying from being too wet. It should be easy to tell which, but don't assume, check the soil with your finger. During drought periods, it may be necessary to water once in a while. A deep watering once or twice a week is much better than frequent watering. Only water when the plants show signs of being dry.

Improper Planting

If the soil is moist and well-drained, then the second most common problem is improper planting. Since the plants may have been planted a number of years earlier, this is a difficult area to consider. However, if a plant has not put out new green shoots in a year, it is dead and you can dig it up and look at the roots. If they are growing in a circle and strangling each other, the plant was not planted properly. You could dig up the other plants and try to open up the roots so they don't strangle each other. If necessary, cut some of the roots so they don't strangle others. If you do dig them up, never let the roots dry out. Dip them in muddy water occasionally while working on them. If they dry out, they will die. Also, never plant rhododendrons and azaleas near black walnut. or butternut trees. Their leaves, nut hulls, and roots produce a toxin called juglone which kills many kinds of plants including rhododendrons and azaleas. Rarefind Nursery has an excellent guide on proper planting of rhododendrons and azaleas.

Soil Nutrients and pH

The third most common cause of decline and death is improper nutrients and pH. Rhododendrons need acidic soil, a pH of between 4.5 and 6. Fortunately, rhododendrons are great pH detectors. If the leaf is green, don't worry. If the leaf is yellow with green veins, you may have a pH problem, however it could be a nutrient problem also. In any case it is chlorotic. [See the photo of a chlorotic leaf.] If the leaf is uniformly yellow, it is most likely a nitrogen deficiency and not chlorosis. There are many causes of chlorosis. Poor drainage, planting too deeply, heavy soil with poor aeration, insect or fungus damage in the root zone and lack of moisture all induce chlorosis. After these conditions are eliminated as possible causes, soil testing is in order. Chlorosis can be caused by malnutrition caused by alkalinity of the soil, potassium deficiency, calcium deficiency, iron deficiency, magnesium deficiency or too much phosphorus in the soil. Iron is most readily available in acidic soils between pH 4.5-6.0. When the soil pH is above 6.5, iron may be present in adequate amounts, but is in an unusable form, due to an excessive amount of calcium carbonate. This can occur when plants are placed too close to cement foundations or walkways. Soil amendments that acidify the soil, such as iron sulfate or sulfur, are the best long term solution. For a quick but only temporary improvement in the appearance of the foliage, ferrous sulfate can be dissolved in water (1 ounce in 2 gallons of water) and sprinkled on the foliage. Some garden centers sell chelated iron that provides the same results. Follow the label recommendations for mixing and applying chelated iron. A combination of acidification with sulfur and iron supplements such as chelated iron or iron sulfate will usually treat this problem. Chlorosis caused by magnesium deficiency is initially the same as iron, but progresses to form reddish purple blotches and marginal leaf necrosis (browning of leaf edges). Epsom salts is a good source of supplemental magnesium. Chlorosis can also be caused by nitrogen toxicity (usually caused by nitrate fertilizers) or other conditions that damage the roots such as root rot, severe cutting of the roots, root weevils or root death caused by extreme amounts of fertilizer. In any case, never use aluminum sulfate. Although garden centers sell it and it is great for hydrangeas, it will kill rhododendrons and azaleas if used repeatedly. Also never use fertilizers with chemical nitrogen. Always use a good rhododendron and azalea fertilizer with organic nitrogen like HollyTone. Also, always fertilize in the spring and at half the rate on the package. If the leaf is uniformly yellow, it is most likely a nitrogen deficiency and not chlorosis. There are many causes of chlorosis. Poor drainage, planting too deeply, heavy soil with poor aeration, insect or fungus damage in the root zone and lack of moisture all induce chlorosis. After these conditions are eliminated as possible causes, soil testing is in order. Chlorosis can be caused by malnutrition caused by alkalinity of the soil, potassium deficiency, calcium deficiency, iron deficiency, magnesium deficiency or too much phosphorus in the soil. Iron is most readily available in acidic soils between pH 4.5-6.0. When the soil pH is above 6.5, iron may be present in adequate amounts, but is in an unusable form, due to an excessive amount of calcium carbonate. This can occur when plants are placed too close to cement foundations or walkways. Soil amendments that acidify the soil, such as iron sulfate or sulfur, are the best long term solution. For a quick but only temporary improvement in the appearance of the foliage, ferrous sulfate can be dissolved in water (1 ounce in 2 gallons of water) and sprinkled on the foliage. Some garden centers sell chelated iron that provides the same results. Follow the label recommendations for mixing and applying chelated iron. A combination of acidification with sulfur and iron supplements such as chelated iron or iron sulfate will usually treat this problem. Chlorosis caused by magnesium deficiency is initially the same as iron, but progresses to form reddish purple blotches and marginal leaf necrosis (browning of leaf edges). Epsom salts is a good source of supplemental magnesium. Chlorosis can also be caused by nitrogen toxicity (usually caused by nitrate fertilizers) or other conditions that damage the roots such as root rot, severe cutting of the roots, root weevils or root death caused by extreme amounts of fertilizer. In any case, never use aluminum sulfate. Although garden centers sell it and it is great for hydrangeas, it will kill rhododendrons and azaleas if used repeatedly. Also never use fertilizers with chemical nitrogen. Always use a good rhododendron and azalea fertilizer with organic nitrogen like HollyTone. Also, always fertilize in the spring and at half the rate on the package.

Insects and Fungi

The least common cause of decline and death is insects and fungi, things that you can spray for. The most common causes are cultural, things that arise because of where and how the plant was planted.  Proper care at planting will usually prevent problems later on due to insects or fungi. One common insect problem that can be avoided is Lace Bugs. [See photo of Lace Bug damage on the underside of a leaf.] Some rhododendrons and azaleas are susceptible to Lace Bug damage. However, this problem can be averted by planting such plants in areas with partial shade. Natural enemies of Lace Bug can keep them in check if the plant doesn’t receive too much sun. Proper care at planting will usually prevent problems later on due to insects or fungi. One common insect problem that can be avoided is Lace Bugs. [See photo of Lace Bug damage on the underside of a leaf.] Some rhododendrons and azaleas are susceptible to Lace Bug damage. However, this problem can be averted by planting such plants in areas with partial shade. Natural enemies of Lace Bug can keep them in check if the plant doesn’t receive too much sun.

For other problems check out my online Guide to Common Problems & Their Solutions

Other Resources

Make sure your neighbor realizes that the local extension service can test soil samples and look at samples of diseased plant material to check for problems. Also, you can help your neighbor find varieties of plants that do well in your area. Unfortunately, some local garden centers stock plants based upon sales appeal rather than on whether they are appropriate for the immediate area. Lists of plants that are known to do well are available in the ARS website’s Proven Performer Lists.

Return to Top

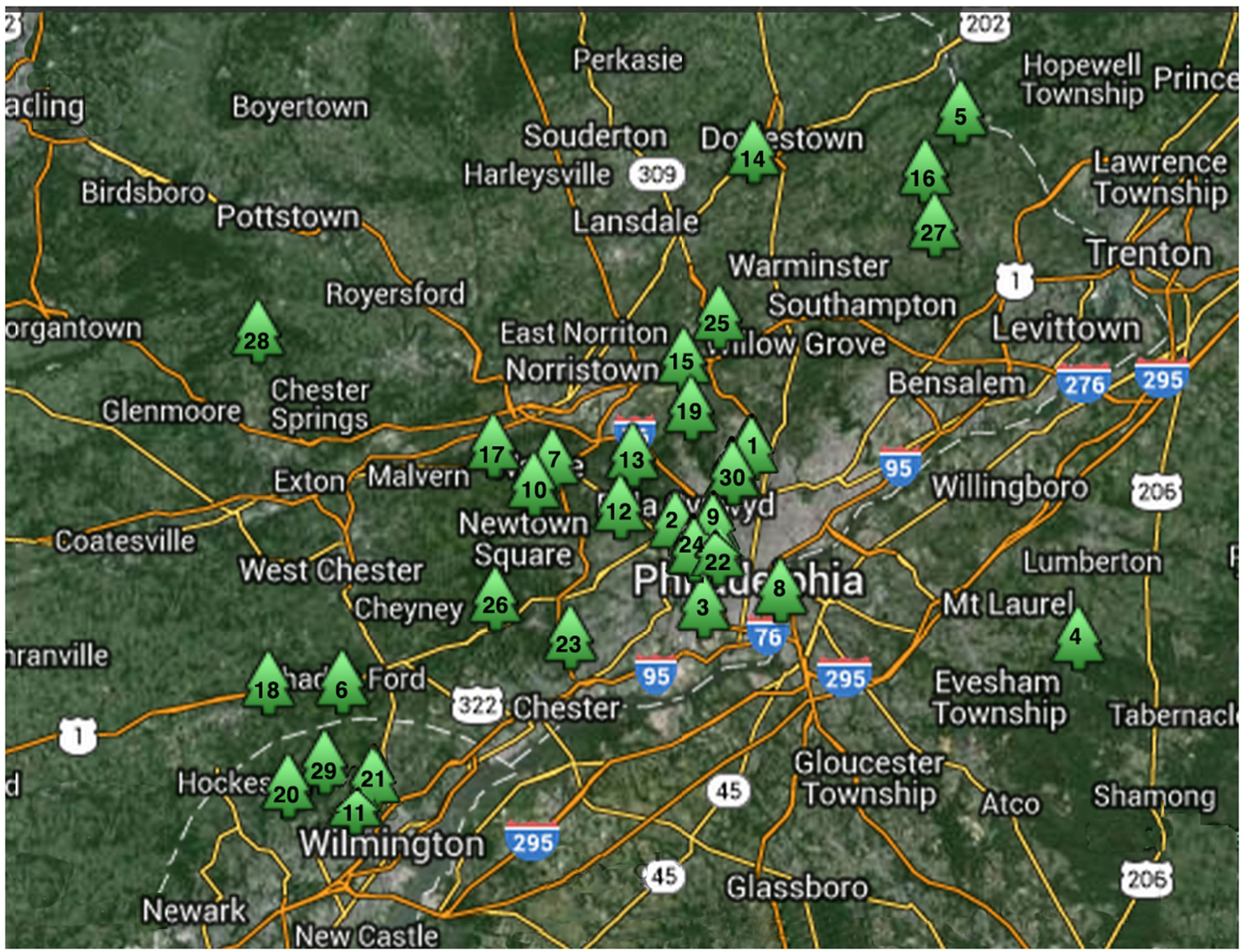

Philadelphia: America’s Garden Capital – 30 Gardens in 30 Miles!

With a tradition of horticulture going back 300 years, Philadelphia is America’s Garden Capital. So much of the nation’s horticultural history is rooted in this region that it has been dubbed “the cradle of horticulture.” Visit more than 30 public gardens, arboreta, and historic landscapes, all located within 30 miles of our landmark city.

1. Awbury Arboretum

A 55-acre natural historic landscape in the historic Germantown section of Phila. |

2. Barnes Foundation

A 12-acre arboretum with over 3,000 species of woody plants and trees in Merion, PA. |

3. Bartram's Garden

The oldest botanic garden in America on the west bank of the Schuylkill, 46 acres. Phila. |

4. Barton Arboretum

Over 200 acres near Medford, NJ, including a nature preserve and gardens. |

5. Bowman's Hill

A 134-acre wildflower preserve in Bucks County near New Hope, PA. |

6. Brandywine River Museum

Brandywine Conservancy’s Wildflower and Native Plant Gardens at Chadds Ford, PA. |

The "du Pont gardens"

• Hagley - E. I. du Pont

• Longwood - Pierre S. du Pont

• Mt. Cuba - Lammot du Pont Copeland

• Nemours- Alfred I. du Pont>

• Winterthur - Henry Francis du Pont

• Chanticleer and Longwood are considered among America’s best public botanical gardens.

• Dating to 1690, Wyck is one of Philadelphia’s oldest houses, although the original log structure is gone.

• Bartram’s garden is America’s oldest botanical garden going back to 1730.

|

|

9. Centennial Arboretum

27 acres in Fairmont Park near the Horticultural Center with gardens and ponds, Phila. |

10. Chanticleer

This former 47-acre estate in Wayne is now one of the premier gardens in the US. |

13. Henry Botanic Garden

50 acres devoted to botanical research in the steep hills of Gladwyne near the Schuylkill. |

14. Henry Schmieder Arboretum

40-acre living collection on the campus of Delaware Valley College, Doylestown, PA. |

15. Highlands Mansion/Garden

44-acre country estate with a mansion and a 2-acre formal garden in Whitemarsh, PA. |

16. Hortulus Farm Garden

100-acre 18th century nursery and farmstead with 30 acres of gardens in Bucks County. |

17. Jenkins Arboretum

46 acres of native trees in Devon, PA, featuring collections of rhododendrons and azaleas. |

18. Longwood Gardens

World famous du Pont 926-acre gardens and conservatory near Kennett Square, PA. |

19. Morris Arboretum

University of Pennsylvania’s 92-acre garden and arboretum in the Chestnut Hill section, Phila. |

20. Mt. Cuba Center

500 acres devoted to native plants with 50 acres of display gardens near Wilmington, DE. |

21. Nemours Mansion/Gardens

3,000-acre du Pont estate and formal gardens with fountains in Wilmington, DE. |

22. Philadelphia Zoo

America's first zoo, a 42-acre Victorian garden, is home to more than 1300 animals. |

23. Scott Arboretum

300 acres on the Swarthmore College Campus with 4,000 kinds of ornamental plants. |

24. Shofuso Japanese Garden

In West Fairmont Park with a 1.2 acre traditional hill-and-pond garden and teahouse. |

25. Temple University Arboretum

187-acre arboretum/campus of the former PA School of Horticulture for Women. |

26. Tyler Arboretum

650 acres near Media, PA, with botanical collections created by Dr. Wister & many trails. |

27. Tyler Formal Gardens

On an acre at the Bucks County Comm. College are 4-tier classical gardens. |

28. Welkinweir

A 197-acres of native plants featuring a 55-acre arboretum in Northern Chester County, PA. |

29. Winterthur

Near Wilmington, DE, its 60-acre naturalistic garden is among America’s best. |

30. Wyck Rose Garden

In Germantown, from the 1820’s. It is the oldest original rose garden in America. |

Return to Top

Don’t let ticks and mosquitoes vector in on you!

- Gnats pester us, ticks bite us and spread disease, and mosquitos do all three. These pests have been especially bad this year.

- Gnats are probably the most benign, but are the peskiest of the three pests. They can spread pink eye, and are extremely annoying.

- Chiggers don't spread disease, but can cause a very annoying and sometimes dangerous allergic reaction.

The CDC and local authorities are on alert for the Zika virus, but it is not a threat in the US yet and especially not in Pennsylvania. Actually ticks are the biggest threat to the gardener in our area with mosquitoes a distant second. They are called vectors because they are biting insects that transmit a disease or parasite from one animal to another. It is important to be aware of what problems they can cause. Pennsylvania has been the Lyme disease capital of the world the last 3 years, and West Nile virus is an emerging threat. We should be able to recognize the symptoms and the vectors causing the problem, especially the ticks. In fact, one of the best weapons against ticks is to make sure we don’t have any attached to our body when we come in from gardening. In addition to that, preventing tick and mosquito bites is very important and fairly easy to do if we think of it in advance.

Which diseases? Which ticks and mosquitos? Protect yourself! What to do if you get bit.

What diseases do they spread?

The diseases caused by ticks and mosquitoes are many and include some nasty ones. If you know you have been bitten by a tick, always tell medical professionals about this when reporting any new symptoms. The symptoms are very non-specific and are often misdiagnosed as a result unless a possible cause is mentioned.

Lyme disease is an infection caused by the spirochete bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi which is transmitted to humans by Blacklegged tick (deer tick) and groundhog tick. It is a complex illness sometimes characterized initially by a bull's eye rash. If you are infected and get the rash, you are lucky since it is easily treated at this stage. If the rash is not present, you can get just about any combination of symptoms including including headache, fever, sore throat, nausea, etc. If left untreated, these can turn into late phase symptoms which may progress to debilitating arthritic, cardiac, and neurologic conditions, but rarely directly to death. There are several tests for Lyme disease, but treatment is often started before test results are in if the bull’s eye rash is present.

The bull's eye rash appears as a red rash and expands to cover a large round region at least 2 inches in diameter over a period of days or weeks. The center of this lesion often tends to progressively clear, giving the name, bull's eye rash. The bull's eye rash is generally accompanied with intermittent fatigue, fever, headache, a stiff neck, muscle aches, and/or joint pain. The joint pain can be mistaken for other types of arthritis, such as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), and neurologic signs of Lyme disease can mimic those caused by other conditions, such as multiple sclerosis (MS) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Early diagnosis is important in preventing late-stage complications. When detected early, Lyme disease can be treated with antibiotics. Left untreated, the disease can spread to the joints, heart and nervous system. Classic signs of untreated cases can include migratory pain or arthritis, impaired motor and sensory skills and an enlarged heart.

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever

Rocky Mountain spotted fever was first recognized in the United States during the 1890s, but until the 1930s it was reported only in the Rocky Mountains. By 1963, over 90 percent of all cases were reported east of the Rockies. In the west, the disease was limited mainly to people who worked and spent time in wooded areas, while in the east, cases occur when people come in contact with infected ticks from their pets or in their yards.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is caused by very small bacteria, Rickettsia rickettsii. The vector in the east is the American dog tick, but the disease is also carried by the Lone star tick and the Rocky Mountain wood tick.

Symptoms include a red-purple-black rash, usually on the wrists and ankles, which appears from two days to two weeks after infection. A fever, headaches, and listlessness also are characteristic. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are used to treat Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Diagnosis can be made with a blood test, but treatment should not wait for lab confirmation, as fatalities do occur.

Also known as rabbit fever, tularemia is carried by the Rocky Mountain wood tick, the Rabbit tick, the Lone star tick, and the American dog tick. Rabbits serve as a reservoir for the bacteria, Francisella tularensis. The number of cases in the United States has dropped considerably in the last 50 years. In 1989 only 144 cases were reported, compared to nearly 2,300 cases in 1939.

Symptoms include a sudden onset of fever, chills, loss of appetite, general body aches, and swollen lymph nodes. An ulcer forms at the site of the bite. Blood tests are used in diagnosis, and treatment consists of antibiotics. If not treated, symptoms intensify. Tularemia causes a few deaths each year.

Caused by the sporozoan parasite, Babesia microti, the disease is transmitted by the Blacklegged tick. Fatigue and loss of appetite are followed by a fever with chills, muscle aches, and headaches. In more extreme cases, blood may appear in the urine. Babesiosis is more severe in older people and those with no spleen. Fatalities can occur in older patients. The condition has been treated with drugs that are used to treat malaria, but with limited success. Generally, the disease is self-limiting and symptoms disappear on their own.

Tick paralysis is not a disease, but a condition caused by toxins that a tick injects into its host during feeding. Most mammals seem to be affected, but smaller and younger mammals, including children, are more susceptible.

Symptoms begin a day or two after initial attachment. The victim loses coordination and sensation in the extremities. The paralysis progresses in severity, the legs and arms becoming useless; the face may lose sensation; and speech becomes slurred. If the breathing center of the brain is affected, the victim may die. If the tick or ticks are found and removed, recovery begins immediately, and the effects disappear within a day.

Generally, this condition is associated with ticks attached around the head area, particularly at the base of the skull. Ticks that have been implicated in tick paralysis in the United States are the Rocky Mountain wood tick, the Lone star tick, and the American dog tick. Some individual ticks cause tick paralysis. The toxin that causes this condition is part of the salivary fluid that the tick injects. Because the problem is associated with ticks attached on the head, and because recovery is quick upon removal of the tick, it is theorized that the toxin acts locally and is broken down in the body rapidly. Tick paralysis occurs only sporadically; the important thing is to be aware that it exists and, when symptoms occur, to attempt to find the tick and remove it.

In Pennsylvania, the risk of contracting a mosquito-borne disease has recently increased with the introduction of West Nile virus. Fortunately, West Nile virus poses little risk to most Pennsylvanians unless they have compromised immune systems.

West Nile virus is a mosquito-borne disease that can cause encephalitis, a brain inflammation. West Nile virus is closely related to St. Louis encephalitis virus which is found in the United States. West Nile virus was first detected in North America in 1999 in New York, and in Pennsylvania in 2000. Prior to that it had only been found in Africa, Eastern Europe, and West Asia.

Infected mosquitoes pass the virus onto birds, animals and people. West Nile virus cases in Pennsylvania occur primarily in the mid-summer or early fall, although mosquito season is usually April-October.

People with mild cases of West Nile virus may experience fever, headache, body aches, skin rash and swollen lymph glands for a few days, the department said, but most people who are infected will not have any type of illness.

Approximately one in 150 people with the virus will develop a more severe form infection known as West Nile encephalitis or meningitis, with symptoms including headache, high fever, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors, convulsions, muscle weakness, and paralysis. In those cases, symptoms may last several weeks, and neurological effects may be permanent.

Which ticks and mosquitoes?

Many species of ticks can transmit diseases from an infected host to other uninfected hosts. Some of the more frequently transmitted organisms include parasitic worms, viruses, bacteria, spirochetes and rickettsias. The most important of these to Pennsylvanians are spirochetes which cause Lyme disease, and rickettsias which cause Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Currently, more than 25 species of ticks have been identified in Pennsylvania. Of these, four species account for nearly 90 percent of all submissions to Penn State for identification. The four ticks are: 1) the American dog tick, Dermacentor variablis; 2) the blacklegged tick, Ixodes scapularis; 3) the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum; and 4) a ground hog tick, Ixodes cookei.

1. American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis

American dog ticks are found predominantly in areas with little or no tree cover, such as grassy fields and scrubland, as well as along walkways and trails. They feed on a variety of hosts, ranging in size from mice to deer, and nymphs and adults can transmit diseases such as Rocky Mountain spotted fever and Tularemia. American dog ticks can survive for up to 2 years at any given stage if no host is found. Females can be identified by their large off-white scutum against a dark brown body. American dog ticks are found predominantly in areas with little or no tree cover, such as grassy fields and scrubland, as well as along walkways and trails. They feed on a variety of hosts, ranging in size from mice to deer, and nymphs and adults can transmit diseases such as Rocky Mountain spotted fever and Tularemia. American dog ticks can survive for up to 2 years at any given stage if no host is found. Females can be identified by their large off-white scutum against a dark brown body.

Adult males and females are active April- early August, and are mostly found questing in tall grass and low lying brush and twigs. They feed on medium-sized wildlife hosts, including raccoons, skunks, opossums and coyotes, as well as domestic dogs, cats and man. Adult American dog ticks commonly attack humans. Male ticks blood feed briefly but do not become distended with blood. Once finished feeding, males mate with the female while she feeds, which can take one week or more. Once engorged, female dog ticks detach from their host and drop into the leaf litter, where they can lay over 4,000 eggs before dying.

Larvae are active late April - September, and can be found questing for a host (voles, mice, raccoons, opossums, etc.) in the leaf litter. In the northeastern U.S., larvae overwinter and are most abundant in the spring and early summer. After blood feeding for 3 to 4 days, larvae detach from their host, falling into the grass/meadow thatch and leaf litter where they molt into nymphs.

Nymphs are active May - July, and feed on small and mid-sized animals, such as mice, voles, rabbits, raccoons and skunks. Nymphal dog ticks rarely attach to humans. Once engorged, nymphs detach from their host, falling into the grass/meadow thatch and leaf litter where they molt into adults.

2. Blacklegged tick, Ixodes scapularis

Blacklegged ticks (a.k.a deer ticks) take 2 years to complete their life cycle and are found predominately in deciduous forest. Their distribution relies greatly on the distribution of its reproductive host, white-tailed deer. Both nymph and adult stages transmit diseases such as Lyme disease, Babesiosis, and Anaplasmosis. Blacklegged ticks (a.k.a deer ticks) take 2 years to complete their life cycle and are found predominately in deciduous forest. Their distribution relies greatly on the distribution of its reproductive host, white-tailed deer. Both nymph and adult stages transmit diseases such as Lyme disease, Babesiosis, and Anaplasmosis.

Adult males and females are active October-May, as long as the daytime temperature remains above freezing. Preferring larger hosts, such as deer, adult blacklegged ticks can be found questing about knee-high on the tips of branches of low growing shrubs. Adult females readily attack humans and pets. Once females fully engorge on their blood meal, they drop off the host into the leaf litter, where they can over-winter. Engorged females lay a single egg mass (up to 1500-2000 eggs) in mid to late May, and then die.

Larvae emerge from eggs later in the summer. Unfed female blacklegged ticks are easily distinguished from other ticks by the orange-red body surrounding the black scutum. Males do not feed. The six-legged larvae are active July-September and can be found in moist leaf litter. Larvae hatch nearly pathogen-free from eggs, and remain in the leaf litter where they will attach to nearly any small, medium or large-sized mammal and many species of birds. Preferred hosts are white-footed mice. Larvae remain attached to their host until replete, which usually requires 3 days. Once fully engorged, the larvae drop off of the host and molt, re-emerging the following spring as nymphs.

Nymphs are active May-August, and are most commonly found in moist leaf litter in wooded areas, or at the edge of wooded areas. The eight-legged, pin-head sized nymph typically attaches to smaller mammals such as mice, voles, and chipmunks, requiring 3-4 days to fully engorge. Nymphs also readily attach to and blood feed on humans, cats and dogs. Once fed, they drop off into rodent burrows or leaf litter in animal bedding areas where they molt and emerge as adults in the fall.

3. Lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum

Lone star ticks are found mostly in woodlands with dense undergrowth and around animal resting areas. The larvae do not carry disease, but the nymphal and adult stages can transmit the pathogens causing Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever and 'Stari' borreliosis. Lone star ticks are notorious pests, and all stages are aggressive human biters. Lone star ticks are found mostly in woodlands with dense undergrowth and around animal resting areas. The larvae do not carry disease, but the nymphal and adult stages can transmit the pathogens causing Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever and 'Stari' borreliosis. Lone star ticks are notorious pests, and all stages are aggressive human biters.

Not only can ticks spread disease, the bite of the Lone Star tick can cause alpha-gal syndrome, an allergy to red meats such as beef and pork, an allergy that doesn't go away with time. A member of the Potomac Valley Chapter is a victim of this allergic response. It makes her allergic to proteins found in red meats such as pork and beef. The fat is OK but not the milk since it has the proteins. There is no cure and the allergic reaction can be life-threatening. What's even more disconcerting is that the Lone Star tick has been spread by deer to all states.

Adults are active April-August and can be found questing for larger animals, such as dogs, coyotes, deer, cattle and humans on tall grass in shade or at the tips of low lying branches and twigs. Females are easily recognized by a single white dot in the center of a brown body, with the males having spots or streaks of white around the outer edge of the body. Females require a week to 10 days or more to engorge and can lay 2,500-3,000 eggs.

Nymphs are active May-August, and can be found questing for deer, coyotes, raccoons, squirrels, turkeys and some birds as well as cats, dogs and humans. Where abundant, nymphs seemingly swarm up pant legs and can become attached in less than 10 minutes. Nymphs typically take 5-6 days to become replete, and once fully engorged, they fall off of the host into the leaf litter, where they molt into adults.

Larvae are active July-September and can be found questing for a wide variety of animals, including cats, dogs, deer, coyotes, raccoons, squirrels, turkeys, and some small birds. After feeding for around 4 days, they drop off of the host and bury themselves in the leaf litter, where they molt into nymphs.

4. Groundhog tick, Ixodes cookei

The groundhog tick, Ixodes cookei, can be found east of the Rocky Mountains into New England and southeast Canada. The tick mostly feeds on rodents and medium-sized mammals, especially groundhogs and skunks. It will feed on a variety of animals including humans. This tick can transmit Powassan virus. The groundhog tick, Ixodes cookei, can be found east of the Rocky Mountains into New England and southeast Canada. The tick mostly feeds on rodents and medium-sized mammals, especially groundhogs and skunks. It will feed on a variety of animals including humans. This tick can transmit Powassan virus.

An adult groundhog tick is about the size of a sesame seed and has a tan body with a reddish-tan plate on its back behind its head. Nymphs and larvae are a lighter tan color and are much smaller than adults. Groundhog ticks feed on small mammals such as skunks, raccoons and groundhogs.

Groundhog tick larvae, nymphs, and adults will readily bite humans and dogs. Groundhog ticks become active in the spring and remain a nuisance through mid-August, with peak activity occurring during late June.

Groundhog ticks may be found in brushy areas and along trails bordered by tall grass or weeds. They are also common in unused human dwellings since these environments are nesting places for small mammals

5. Northern house mosquito, Culex pipiens

Pennsylvania has 60 species of mosquitoes. The mosquito most often discovered in urban areas of Pennsylvania is the northern house mosquito, Culex pipiens. This is also the mosquito that is thought to transmit the most human cases of West Nile virus in Pennsylvania and consequently poses the greatest annoyance and risk to our citizens. Pennsylvania has 60 species of mosquitoes. The mosquito most often discovered in urban areas of Pennsylvania is the northern house mosquito, Culex pipiens. This is also the mosquito that is thought to transmit the most human cases of West Nile virus in Pennsylvania and consequently poses the greatest annoyance and risk to our citizens.

Some mosquito species can complete their life cycles in as little as 7 days but the northern house mosquito requires a minimum of 10-14 days – more often closer to a month.

Adult female mosquitoes require a blood meal in order to produce viable eggs. While feeding, the females inject saliva-containing anticoagulants that prevent the blood from clotting. Because mosquitoes take numerous blood meals, they can acquire disease organisms from an infected host and later transmit those organisms to previously uninfected hosts.

Considered to be a medium-sized mosquito, the adult Culex pipiens may reach up ¼”. The House mosquito species' body is usually brownish or grayish brown. The proboscis and wings are usually brown.

Larvae are known as wigglers since they seem to move in that manner. They feed on fungi, bacteria and other tiny organisms through straw-like filters. These larvae will undergo growth throughout this stage.

Pupae are known as tumblers because of the way they seem to “tumble” through the water. Their rounded, comma-like shape makes this mode of movement easy. These pupae do not eat during the 1-2 days in which they will become an adult mosquito.

Control of this mosquitoes is achieved through meticulous removal of water holding containers. Birdbaths and pet bowls should be scrubbed and the water changed at least every few days. For the gardener, check stacks of pots and saucers that are exposed to rain and make sure they are dry. The homeowner needs to ensure that gutters and downspouts are free of leafy debris that might retain rainwater. Still-water ponds, water features, and wet ditches can be treated with the biological control, Bacillus thuringiensis israelenis, sold as Mosquito Dunks or Mosquito Bits.

Protect yourself!

Avoiding tick bites is very important, especially in areas near where deer are prevalent. The best advice for preventing Lyme disease, West Nile virus, and other tick and mosquito-borne diseases is to:

1. Wear treated light-colored SPF clothing while outdoors, including a broad-brimmed hat, a long-sleeved shirt, and long pants tucked into the socks. Permethrin treated clothing will kill ticks that are crawling. Spray-on applications can last 5 or 6 washing. You can also buy pre-treated clothing that has been tested and proven to be effective at up to 25 washing cycles. This works for chiggers also. Chigger may not be dangerous, but their bite sure is annoying. Note, permethrin sprays are ineffective when applied to human skin. Permethrin is for use on clothing only. It does not harm or irritate skin, but it offers no benefits if applied to skin. It is considered totally safe to people, the environment, and to clothing.

2. Check your body daily for the presence of ticks. Self-examination is recommended after spending time in infested areas. If an embedded tick is found, it should be removed with fine tweezers by grasping the head and pulling with steady firm pressure. The tick should not be grabbed in the middle of its body because the gut contents may be expelled into the skin. The use of heat (lit match, cigarette, etc.), or petroleum jelly is NOT recommended to force the tick out. These methods will irritate the tick, and may cause it to regurgitate its stomach contents into the individual, thereby increasing the possibility of infection.

3. Use tick & mosquito repellents. DEET, Picaridin, Oil of lemon eucalyptus have proven to repel both ticks and mosquitoes for up to 8 hours. These are the most effective formulations. Weaker formulations protect for shorter periods of time.

- 30 to 40% DEET such as Sawyer Ultra 30 and 3M Ultrathon offer up to 12 hours protection. WARNING: DEET can damage plastics but will not damage cotton, wool or nylon. For children, do not use concentrations stronger than 30%. Do not apply to open cuts.

- Picaridin was developed as an alternative to DEET. With a concentration of 20%, Sawyer Picaridin offers up to 8 hours protection. Care should be taken when using near plastics.

- Oil of Lemon Eucalyptus such a Repel 30% Lemon Eucalyptus provides up to 7 hours protection. It is totally safe around all materials and people. It is an ingredient in Vicks VapoRub.

- Natural Plant Oils such as citronella, cedar, geranium, etc. offer limited protection.

These repellents can also be applied to clothing and are more effective than the permethrin sprays sold for that purpose. However, always test DEET on a small spot before applying to clothing since it will damage plastics, rubber, leather, vinyl, paint, and some synthetic fabrics such as acetate, rayon, spandex and Gortex. It does not damage cotton, wool, or nylon. Picaridin and Lemon Eucalyptus can also be used on clothing and will not damage fabrics.

The first line of defense against ticks and mosquitoes is to take precautions in the outdoors by using insect repellents, wearing long sleeve shirts and long pants treated with permethrin, checking for - and promptly and properly removing – any ticks, and showering shortly after exposure.

4. Avoiding swarming pests The repellents that prevent bites from mosquitos and ticks don't always prevent gnats and mosquitos from being a pest and swarming around your head. If you would rather avoid putting DEET and other chemicals on your skin, do what bee keepers have been doing for centuries, use a head net.

Head nets have been refined and come in a model by womanswork.com as well as many other models. They come as netting that goes over a broad brimmed hat as well as hats with netting attached. It may seem like overkill to use a head net, but anything that keeps the gnats and more dangerous insects at bay is OK with me.

What to do if you get bit.

Tick Bites. Usually, removing the tick, washing the site of the bite, and watching for signs of illness are all that is needed. When you have a tick bite, it is important to determine whether you need a tetanus shot to prevent tetanus (lockjaw).

Many of the diseases ticks carry cause flu-like symptoms, such as fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and muscle aches. Symptoms may begin from 1 day to 3 weeks after the tick bite. Sometimes a rash or sore appears along with the flu-like symptoms. Tick paralysis is a rare problem that may occur after a tick bite.

Though rare, tick bites can trigger a severe anaphylaxis reaction. If epinephrine is available, do not hesitate to use it. Using an epinephrine auto-injector as a precaution will not harm you and could save your life. Call 911 after using the EpiPen.

Call your doctor or seek immediate medical care if:

- You have signs of infection, such as:

- Increased pain, swelling, warmth, or redness around the bite.

- Red streaks leading from the bite.

- Pus draining from the bite.

- A fever.

Watch closely for changes in your health, and be sure to contact your doctor if:

- You develop a new rash.

- You have joint pain.

- You are very tired.

- You have flu-like symptoms.

- You have symptoms for more than 1 week.

Mosquito Bites. Mosquito bites can be an itchy nuisance. They'll go away on their own. If you need relief in the meantime, apply a hydrocortisone cream or calamine lotion to the bite. A cold pack or baggie filled with crushed ice may help, too.

In the United States, mosquitoes can spread West Nile virus. For about 80% of people who are infected, this virus causes no symptoms. But in some people, West Nile virus can cause severe illness and even death. Those more at risk for getting sick from West Nile virus are people aged 50 and older.

In mild cases, symptoms may include:

- Fever

- Body aches

- Headache

- Vomiting

- Swollen glands

Serious symptoms require a doctor's care. They include:

- High fever

- Muscle weakness

- Vision loss

- Neck stiffness

- Disorientation or stupor

- Tremors, convulsions, numbness, paralysis

Symptoms usually occur three days to two weeks after a bite from an infected mosquito. If you notice any severe symptoms, see your doctor right away. You can usually treat less severe symptoms, such as a mild fever or headache, at home.

Return to Top

References: Books Used In Preparing This Site Listed by Title

- "All About Azaleas, Camellias & Rhododendrons (Ortho)" by Fell, Derek snf Fred Galle, Gary Hespenheide, (2001)

- "American Azaleas" by Towe, L. Clarence (2004)

- "American Rhododendron Hybrids" by Kraxberger, Meldon,editor (1980)

- "Azakeas, Kinds and Culture" by Hume, H. Harold (1954)

- "Azalea Book, The," by Lee, Frederic Paddock (1958)

- "Azalea Book, The," by Lee, Frederic Paddock (1980)

- "Azalea Handbook, The," by Lee, Coe, Morrison (1953)

- "Azaleas and Camelias" by Hume, H. Harold (1931)

- "Azaleas, Camelias, and Rhododendrons (Ortho)" by Reilley, H. Edward (2001)

- "Azaleas" by Fairweather, Christopher (1988)

- "Azaleas" by Galle, Fred C. (1988)

- "Big Leaf Rhododendrons: Growng the Giants of the Genus *NEW*" by Church, Glyn and Graham Smith, & Pat Greenfield (2015)

- "Book of Rhododendrons, The," by Kneller, Marianna (1995)

- "Brocade Pillow: Azaleas of Old Japan, A," by Ito, Iheo (1984)

- "Catalogue" by Whitney Gardens and Nursery (2013)

- "Compendium of Rhododendron and Azalea Diseases *NEW*" by Linderman, Robert G. and Dr. Michael Benson (2014)

- "Compendium of Rhododendron and Azalea Diseases" by Coyier, Duane and Martha Roane (1986)

- "Contributions Toward A Classificationof Rhododendrons" by Luteyn, James L. (1978)

- "Cox's Guide to Choosing Rhododendrons" by Cox, Peter and Kenneth Cox (1995)

- "Crossing the Rubicon" by Coker, Brian (1998)

- "Cultivation of Rhododendrons, The," by Cox, Peter A. (1994)

- "Dexter Estate, The," by Cowels, Evelyn (1986)

- "Dwarf Rhododendrons" by Cox, Peter A. (1973)

- "Encyclopedia of Rhododendron Hybrids" by Cox, Peter A. Cox, Kenneth N.E. (1988)

- "Encyclopedia of Rhododendron Species" by Cox, Peter A. Cox, Kenneth N.E. (2001)

- "Fungi on Rhododendron : A World Reference" by Palm, Farr, Esteban, and (1996)

- "Gardening With Rhododendrons" by Richards, Murray (1994)

- "Getting Started With Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by Clarke, Jay Harold (1983)

- "Glenn Dale Azaleas, The," by Morrison, B. Y. (1953)

- "Great American Azaleas" by Darden, Jim (1985)

- "Greer's Guidebook to Available Rhododendrons" by Greer, Harold E. (1996)

- "Greer's Guidebook to Rhododendrons" by Greer, Harold E. (1982)

- "Growing Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by Bryant, Geoff (1996)

- "Growing Rhododendrons in New England" by Parks, J. B. (1999)

- "Growing Rhododendrons, A Garden Guide (Pukeiti)" by Harrup, David (1996)

- "Growing Rhododendrons" by Francis, Richard (1998)

- "Guide to Rhododendrons, A," by Cox, Kenneth (2005)

- "Handbook of Rhododendrons, The," by Frye, Nearing, Cox, Bowers, et.al. University of Washington (1946)

- "Hardy Rhododendron Species" by Cullen, James (2005)

- "Hardy Rhododendrons" by Street, Frederick (1955)

- "Himalayan Garden, The," by Jermyn, Jim (2001)

- "History of the Rhododendron Species: Genesis of a Botanic Garden" by Clarence Barrett Foundation (1994)

- "How To Identify Rhododendron And Azalea Problems" by Antonelli, Art (1999)

- "Hybrids and Hybridizers, Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by Livingston, Philip A. and Franklin H. West (1978)

- "Identifying, Treating & Avoiding Azalea and Rhododendron Problems" by Scott, (WSU) (2015)

- "Illustrated Rhododendron: Portrayed Through the Artwork of Curtis's Botanical Magazine" by Halliday, Pat and John Curtis (Illustrator) (2001)

- "Kalmia : Mountain Laurel and Related Species" by Jaynes, Richard A. (1997)

- "Larger Rhododendron Species" by Cox, Peter A. (1990)

- "Laurel Book, The" by Jaynes, Richard A. (1974)

- "Making the most of Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by Fairweather, Christopher (1993)

- "Making the most of Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by Fairweather, Christopher (1993)

- "Modern Rhododendrons" by Cox, E. H. M. and P. A. Cox (1956)

- "Monograph on Azaleas, A," by Wilson, Ernest Henry (1921)

- "Native and Introduced Azaleas for Southern Gardens" by Galle, Fred (1962)

- "Pacific Coast Rhododendron Story, The," by Nelson, Sonja (Compiler) (2001)

- "Phenology of Cultivated Rhododendrons" by Wade, L. Keith (1965)

- "Plantsman's Guide to Rhododendrons, A," by Cox, Kenneth (2008)

- "Plantsman's Paradise, Travels in China" by Lancaster, Roy * (2008)

- "Pocket Guide to Rhododendron Species" by McQuire, J. F. and Robinson, M.L.A. (2010)

- "Production of Florist Azaleas (Growers Handbook, Vol 6)" by Armitage, Allan M. and Roy A. Larson (2003)

- "Public Rhododendron gardens of Vancouver Island *NEW*, The," by Efford, Ian E. with Alan Campbell & Susan Lightburn * (2015)

- "Pukeiti: New Zealand's Finest Rhododendron Garden" by Greenfield, Pat (1997)

- "Resplendence of Rhododendrons, A," by McCarter and Fuller (2005)

- "Rhododendron Basics" by Greer, Harold E. * (1996)

- "Rhododendron Handbook, Rhododendron Species in Cultivation, The," by Royal Horticultural Society (1980)

- "Rhododendron Hybrids" by Salley, Homer E. and Harold E. Greer (2005)

- "Rhododendron Information" by American Rhododendron Society (Jay Harold Clarke) (1967)

- "Rhododendron Leaf - A Study of the Epidermal Appendages, The," by Cowan, J. M. (1950)

- "Rhododendron Notes" by American Rhododendron Society (Jay Harold Clarke) (1968)

- "Rhododendron Pocketbook, The," by Cooper, W. E. Shewell- (1955)

- "Rhododendron Portraits" by Van Gelderen, D.M. (2005)

- "Rhododendron Species : Azaleas Vol 4, The," by Davidian, H. H. (2003)

- "Rhododendron Species : Vol 3 Elepidotes Neriiflorum-Thomsonii, The," by Davidian, H. H. (1982)

- "Rhododendron Species Dictionary" by Spady, Herbert A. (1984)

- "Rhododendron Species, Vol 1: Lepidotes" by Davidian, H.H. (2003)

- "Rhododendron Species, Vol 2 Part 1 : Elepidotes, Arboreum-Lacteum" by Davidian, H.H. (2003)

- "Rhododendron Species: 2006" by Rhododendron Species Foundation (2006)

- "Rhododendron Species: 2007" by Rhododendron Species Foundation (2007)

- "Rhododendron Species: 2008" by Rhododendron Species Foundation (2008)

- "Rhododendron Species: 2009" by Rhododendron Species Foundation (2009)

- "Rhododendron Species: 2010" by Rhododendron Species Foundation (2010)

- "Rhododendron Species: 2013" by Rhododendron Species Foundation (2013)

- "Rhododendron Story, The," by Postan, Cynthia (1996)

- "Rhododendron Yearbook for 1945, The," by American Rhododendron Society (Dean Collins) (1945)

- "Rhododendron Yearbook for 1946, The," by American Rhododendron Society (Dean Collins) (1946)

- "Rhododendron Yearbook for 1947, The," by American Rhododendron Society (Robert Moulton Gatke) (1947)

- "Rhododendron Yearbook for 1948, The," by American Rhododendron Society (Robert Moulton Gatke) (1948)

- "Rhododendron Yearbook for 1949, The," by American Rhododendron Society (Robert Moulton Gatke) (1949)

- "Rhododendron-Park Bremen" by Monch, Jochen and Hartwig Schepker (2010)

- "Rhododendron, Azaleas, Magnolias, Camelias, and Ornamental Cherries" by Johnson, A. T. and F. C. Puddle (1948)

- "Rhododendrons (RHS/Wisley)" by Cox, Peter A. (1992)

- "Rhododendrons (The New Plant Library)" by Hawthorne, Lin (1999)

- "Rhododendrons (Wisley)" by Cox, Peter A. (1980)

- "Rhododendrons 1956" by American Rhododendron Society (Jay Harold Clarke) (1956)

- "Rhododendrons and Azaleas (Present Day Gardening)" by Watson, William (?)

- "Rhododendrons and Azaleas (Sunset)" by Eddinger, Philip (1999)

- "Rhododendrons and Azaleas: A Colour Guide" by Cox, Kenneth (2005)

- "Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by Berrisford, Judith Mary (1973)

- "Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by Bonar, Ann (1993)

- "Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by Bowers, Clement Gray (1960)

- "Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by Bryant, Geoff (2001)

- "Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by Kessell, Mervyn (1982)

- "Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by La Croix, I. F. (1973)

- "Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by Street, Frederick (1957)

- "Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by Watson, William (?)

- "Rhododendrons and Magnolias" by Bartrum, Douglas (1957)

- "Rhododendrons for Amatuers" by Cox, E. H. M. (1924)

- "Rhododendrons for Every Garden" by Wakefield, Geoffrey R. (1965)

- "Rhododendrons for Everyone" by Wakefield, Geoffrey R. (1926)

- "Rhododendrons for Your Garden" by American Rhododendron Society (Jay Harold Clarke) (1961)

- "Rhododendrons in America" by Van Veen, Ted (1980)

- "Rhododendrons in New Zealand" by Tapley, Mrgaret (1989)

- "Rhododendrons in the Landscape" by Nelson, Sonja (2000)

- "Rhododendrons of China" by Guomei, Feng * (1992)

- "Rhododendrons of China" by Guomei, Feng & Yang Zenghong, Guo-Mei Feng (Editors) * (1999)

- "Rhododendrons of China" by Young, Judy and Lu-Sheng Chong (1981)

- "Rhododendrons of Darjeeling and Sikkim Himalayas" by Sain, M. (1974)

- "Rhododendrons of Milner Gardens and Woodland, The," by Milner Gardens (?)

- "Rhododendrons of the World" by Leach, David G. (1961)

- "Rhododendrons You Should Meet" by Van Veen, Ted (1996)

- "Rhododendrons, A Guide to Selecting and Enjoying" by Rhodes, Janet (1982)

- "Rhododendrons: A Care Manual" by Cox, Kenneth and N. E. Cox, Laurel Glen (1998)

- "Rhododendrons" by Cox, Peter Alfred (1989)

- "Rhododendrons" by Krüssmann, Gerd (1970)

- "Rhododendrons" by Street, Frederick (1965)

- "Rhododendrons" by Street, John (1987)

- "Rhododendrons" by Wakefield, Geoffrey R. (1950)

- "Riddle of the Tsangpo Gorges" by Ward, Frank Kingdon & Kenneth Cox, Ken Storm Jr., Ian Baker (2008)

- "Rothschild Gardens, The," by Rothschild DSc, Miriam & Andrew Lawson, Kate Garton, Lionel de Rothschild (2000)

- "Rothschild Rhododendrons: The Gardens at Exbury" by Phillips, C. E. Lucas and Peter Barber (1979)

- "Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh 2008" by Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh (2008)

- "Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh 2009" by Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh (2009)

- "Satsuki Azaleas for Bonsai and Azalea Enthusiasts" by Callaham, Robert Z * (2006)

- "Seeds of Adventure, In Search of Plants" by Cox, Peter and Peter Hutchison * (2008)

- "Selected Rhododendron Glossary and Botanical Terms" by Nelson, Pat and Marlene Buffington, Nadine Henry (1982)

- "Sikkim and the World of Rhododendrons" by Pradham, Udai C. and Sonam T. Lachungpa (1990)

- "Smaller Rhododendrons, The," by Cox, Peter A. (1990)

- "Southern Living Azaleas" by Galle, Fred (1974)

- "Species of Rhododendrons, The," by Stevenson, J. B. (The Rhododendron Society) (1947)

- "Study of Species for New England, A," by Masschussetts Chapter, ARS (2000)

- "Success with Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by Kosel, Andrea (1999)

- "Success with Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by Reilley, H. Edward (2004)

- "Tales of the Rose Tree" by Brown, Jane (2006)

- "Titere Gardens, Rotorua" by Robertson, B. R. (1998)

- "Top-Rated Azaleas and Rhododendrons (Golden)" by Latimer (Horticulturalist Associates Inc.) (1983)

- "Vireya Rhododendrons" by Smith, E. W. (1998)

- "Vireyas: A Practical Gardening Guide" by Kenyon, John and Jacqueline Walker (2003)

- "Winter Hardy Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by Bowers, Clement Gray (1954)

- "Winter Hardy Rhododendrons and Azaleas" by Bowers, Clement Gray (1954)

- "Wit and Wisdom of Norman Todd" by Todd, Norman (2011)

- "Woody Ornamental Insect, Mite & Disease Management" by Hock, (Penn State) (1995)

References Listed By Title

References Listed By Author

Return to Top

References: Books Used In Preparing This Site Listed By Author

- American Rhododendron Society (Dean Collins): "Rhododendron Yearbook for 1945, The," (1945)

- American Rhododendron Society (Dean Collins): "Rhododendron Yearbook for 1946, The," (1946)

- American Rhododendron Society (Jay Harold Clarke): "Rhododendron Information" (1967)

- American Rhododendron Society (Jay Harold Clarke): "Rhododendron Notes" (1968)

- American Rhododendron Society (Jay Harold Clarke): "Rhododendrons 1956" (1956)

- American Rhododendron Society (Jay Harold Clarke): "Rhododendrons for Your Garden" (1961)

- American Rhododendron Society (Robert Moulton Gatke): "Rhododendron Yearbook for 1947, The," (1947)

- American Rhododendron Society (Robert Moulton Gatke): "Rhododendron Yearbook for 1948, The," (1948)

- American Rhododendron Society (Robert Moulton Gatke): "Rhododendron Yearbook for 1949, The," (1949)

- Antonelli, Art: "How To Identify Rhododendron And Azalea Problems" (1999)

- Armitage, Allan M. and Roy A. Larson: "Production of Florist Azaleas (Growers Handbook, Vol 6)" (2003)

- Bartrum, Douglas: "Rhododendrons and Magnolias" (1957)

- Berrisford, Judith Mary: "Rhododendrons and Azaleas" (1973)

- Bonar, Ann: "Rhododendrons and Azaleas" (1993)

- Bowers, Clement Gray: "Rhododendrons and Azaleas" (1960)

- Bowers, Clement Gray: "Winter Hardy Rhododendrons and Azaleas" (1954)

- Bowers, Clement Gray: "Winter Hardy Rhododendrons and Azaleas" (1954)

- Brown, Jane: "Tales of the Rose Tree" (2006)

- Bryant, Geoff: "Growing Rhododendrons and Azaleas" (1996)

- Bryant, Geoff: "Rhododendrons and Azaleas" (2001)

- Callaham, Robert Z *: "Satsuki Azaleas for Bonsai and Azalea Enthusiasts" (2006)

- Church, Glyn and Graham Smith, & Pat Greenfield: "Big Leaf Rhododendrons: Growng the Giants of the Genus *NEW*" (2015)

- Clarence Barrett Foundation: "History of the Rhododendron Species: Genesis of a Botanic Garden" (1994)

- Clarke, Jay Harold: "Getting Started With Rhododendrons and Azaleas" (1983)

- Coker, Brian: "Crossing the Rubicon" (1998)

- Cooper, W. E. Shewell-: "Rhododendron Pocketbook, The," (1955)

- Cowan, J. M.: "Rhododendron Leaf - A Study of the Epidermal Appendages, The," (1950)

- Cowels, Evelyn: "Dexter Estate, The," (1986)

- Cox, E. H. M. and P. A. Cox: "Modern Rhododendrons" (1956)

- Cox, E. H. M.: "Rhododendrons for Amatuers" (1924)

- Cox, Kenneth and N. E. Cox, Laurel Glen: "Rhododendrons: A Care Manual" (1998)

- Cox, Kenneth: "Guide to Rhododendrons, A," (2005)

- Cox, Kenneth: "Plantsman's Guide to Rhododendrons, A," (2008)

- Cox, Kenneth: "Rhododendrons and Azaleas: A Colour Guide" (2005)

- Cox, Peter A. Cox, Kenneth N.E.: "Encyclopedia of Rhododendron Hybrids" (1988)

- Cox, Peter A. Cox, Kenneth N.E.: "Encyclopedia of Rhododendron Species" (2001)

- Cox, Peter A.: "Cultivation of Rhododendrons, The," (1994)

- Cox, Peter A.: "Dwarf Rhododendrons" (1973)

- Cox, Peter A.: "Larger Rhododendron Species" (1990)

- Cox, Peter A.: "Rhododendrons (RHS/Wisley)" (1992)

- Cox, Peter A.: "Rhododendrons (Wisley)" (1980)

- Cox, Peter A.: "Smaller Rhododendrons, The," (1990)

- Cox, Peter Alfred: "Rhododendrons" (1989)

- Cox, Peter and Kenneth Cox: "Cox's Guide to Choosing Rhododendrons" (1995)

- Cox, Peter and Peter Hutchison *: "Seeds of Adventure, In Search of Plants" (2008)

- Coyier, Duane and Martha Roane: "Compendium of Rhododendron and Azalea Diseases" (1986)

- Cullen, James: "Hardy Rhododendron Species" (2005)

- Darden, Jim: "Great American Azaleas" (1985)

- Davidian, H. H.: "Rhododendron Species : Azaleas Vol 4, The," (2003)

- Davidian, H. H.: "Rhododendron Species : Vol 3 Elepidotes Neriiflorum-Thomsonii, The," (1982)

- Davidian, H.H.: "Rhododendron Species, Vol 1: Lepidotes" (2003)

- Davidian, H.H.: "Rhododendron Species, Vol 2 Part 1 : Elepidotes, Arboreum-Lacteum" (2003)

- Eddinger, Philip: "Rhododendrons and Azaleas (Sunset)" (1999)

- Efford, Ian E. with Alan Campbell & Susan Lightburn *: "Public Rhododendron gardens of Vancouver Island *NEW*, The," (2015)

- Fairweather, Christopher : "Azaleas" (1988)

- Fairweather, Christopher: "Making the most of Rhododendrons and Azaleas" (1993)

- Fairweather, Christopher: "Making the most of Rhododendrons and Azaleas" (1993)

- Fell, Derek snf Fred Galle, Gary Hespenheide: "All About Azaleas, Camellias & Rhododendrons (Ortho)" (2001)

- Francis, Richard: "Growing Rhododendrons" (1998)

- Frye, Nearing, Cox, Bowers, et.al. University of Washington: "Handbook of Rhododendrons, The," (1946)

- Galle, Fred C.: "Azaleas" (1988)

- Galle, Fred: "Native and Introduced Azaleas for Southern Gardens" (1962)

- Galle, Fred: "Southern Living Azaleas" (1974)

- Greenfield, Pat: "Pukeiti: New Zealand's Finest Rhododendron Garden" (1997)

- Greer, Harold E. *: "Rhododendron Basics" (1996)

- Greer, Harold E.: "Greer's Guidebook to Available Rhododendrons" (1996)

- Greer, Harold E.: "Greer's Guidebook to Rhododendrons" (1982)

- Guomei, Feng *: "Rhododendrons of China" (1992)

- Guomei, Feng & Yang Zenghong, Guo-Mei Feng (Editors) *: "Rhododendrons of China" (1999)

- Halliday, Pat and John Curtis (Illustrator) : "Illustrated Rhododendron: Portrayed Through the Artwork of Curtis's Botanical Magazine" (2001)

- Harrup, David: "Growing Rhododendrons, A Garden Guide (Pukeiti)" (1996)

- Hawthorne, Lin: "Rhododendrons (The New Plant Library)" (1999)

- Hock, (Penn State): "Woody Ornamental Insect, Mite & Disease Management" (1995)

- Hume, H. Harold: "Azakeas, Kinds and Culture" (1954)

- Hume, H. Harold: "Azaleas and Camelias" (1931)

- Ito, Iheo: "Brocade Pillow: Azaleas of Old Japan, A," (1984)

- Jaynes, Richard A.: "Kalmia : Mountain Laurel and Related Species" (1997)

- Jaynes, Richard A.: "Laurel Book, The" (1974)

- Jermyn, Jim: "Himalayan Garden, The," (2001)

- Johnson, A. T. and F. C. Puddle: "Rhododendron, Azaleas, Magnolias, Camelias, and Ornamental Cherries" (1948)

- Kenyon, John and Jacqueline Walker: "Vireyas: A Practical Gardening Guide" (2003)

- Kessell, Mervyn: "Rhododendrons and Azaleas" (1982)

- Kneller, Marianna: "Book of Rhododendrons, The," (1995)

- Kosel, Andrea: "Success with Rhododendrons and Azaleas" (1999)

- Kraxberger, Meldon,editor: "American Rhododendron Hybrids" (1980)

- Krüssmann, Gerd: "Rhododendrons" (1970)

- La Croix, I. F.: "Rhododendrons and Azaleas" (1973)

- Lancaster, Roy *: "Plantsman's Paradise, Travels in China" (2008)

- Latimer (Horticulturalist Associates Inc.): "Top-Rated Azaleas and Rhododendrons (Golden)" (1983)

- Leach, David G.: "Rhododendrons of the World" (1961)

- Lee, Coe, Morrison: "Azalea Handbook, The," (1953)